“Island magic works on Island souls.”

Observed by Sabine Strohem, a character in Nick Bantock’s bestselling book, Griffin & Sabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence (Chronicle Books, 1991).

I live on Saltspring Island, but I’m a frequent floater. During the week, I commute on BC Ferries from Fulford village, on the island’s south end, to my job in downtown Victoria.

Happily, today is Saturday. I don’t have to rush to catch the Skeena Queen before she shudders away from the dock. I’m in Fulford to collaborate with renowned author and illustrator Nick Bantock, a fellow Saltspringer.

The island is known for its abundance of artists, from potters and painters to jewellers and woodworkers. Bantock, who opened a studio gallery here in 2007, has promised to show me Saltspring through a different lens. If our afternoon drive is anything like the wonderfully strange escapes provided by his fiction, I’m in for quite a ride.

While Bantock and his wife, fabric artist Joyce Greig, now enjoy a relatively quiet life on Saltspring, the fame that followed the release of his Griffin & Sabine trilogy was also quite a ride. The books, which employ artful postcards and removable letters to convey a fictional love affair-by-correspondence, captivated readers worldwide. Suddenly, Bantock was a media sensation, a talk-show celebrity. Two of his titles dominated the New York Times bestseller list in 1992, and the books sold millions of copies.

I spot him in the parking lot of Patterson Market, Fulford’s 72-year-old general store. He’s dressed in a charcoal grey sweater and jeans, leaning against a shiny red convertible Mini Cooper. Bantock grins mischievously as I approach, his eyebrows shooting upward.

“Great car,” I say, as I slip into the black leather passenger seat. This is going to be fun.

The roads on Saltspring are a lot like those in Bantock’s native England: narrow and winding, sometimes potholed. This can be annoying if you’re in a rush or you value your car’s suspension. The key, islanders soon learn, is not to be in a rush in the first place.

The pace on Saltspring is slow, as handpainted blue signs around the island gently urge.

At just under 200 square kilometres, Saltspring is the largest of the southern Gulf Islands. That’s a lot of ground for us to cover, and my instinct is to plan out a route on our map. But Bantock convinces me to let our drive simply unfold, free of expectations.

“Let’s just follow our whims,” he says, putting the car in reverse. “Where there’s a Whims,” he adds playfully, referring to Whims Road on north Saltspring, “there’s a way.”

We motor uphill from the ferry terminal, past flowering shrubs and rambling blackberry bushes that seem almost Mediterranean. We turn onto Beaver Point Road, heading east past the apple orchards and rocky pastures of some of Saltspring’s first farms. Just before Stowell Lake, we see one of the island’s many unmanned farm stands, offering fresh produce in exchange for payment to an “honour box.”

Beyond the junction with Stewart Road, dense stands of Douglas fir shade our route. Bantock clearly enjoys navigating the Mini on these less-travelled roadways.

“The car loves it here,” he says, dodging a pothole.

Daylight returns as we descend into the open pastures of Ruckle Provincial Park, a 4.86-square-kilometre seaside site that includes coastal hiking trails, camping and picnic facilities, and British Columbia’s oldest continually operating farm, circa 1872.

We park the car in a forested area and, breathing in the fragrance of western redcedars, walk to a moss-covered promontory overlooking Swanson Channel. A BC Ferries vessel glides across the horizon.

“Ferries are like a bridge from the mainland,” Bantock reflects. “They take us from everything it offers to a place where tensions are palpably reduced. From the moment you set foot on Saltspring, you sense that you can relax.”

We backtrack to Fulford, pass the ferry terminal, and pull off at St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church. Built in the 1880s, this small stone-faced house of worship is Saltspring’s oldest church. From its steps, we watch the Skeena Queen enter Fulford Harbour. Some of the early Hawaiian settlers who helped build St. Paul’s are buried in the cemetery here, their graves marked with shell necklaces. We walk a stretch of beach down the road and below the church, where these settlers once held their traditional luaus.

“This area is so historically evocative,” says Bantock, as he pockets a stone, a twig, and a shell—future materials for one of his eclectic works of art.

“It’s about looking and feeling,” the artist observes. “When you look around you and fully concentrate on your senses, suddenly a place becomes so much more.”

We return to the Mini and continue on Beaver Point Road, past the Fulford Inn, to the intersection with Saltspring’s main artery, Fulford-Ganges Road—a good, wide road, arguably the island’s best. We increase our speed slightly, passing Fulford Community Hall, the fire hall, and several south-end farms.

We slow again as the unmistakable outline of Mount Maxwell rises before us. Flipping on his four-way flashers, Bantock pulls over and we gaze up at the peak’s notched profile. From our perspective, its ancient rock face seems bearded with a thick growth of fir trees.

Beyond the turnoff to Burgoyne Bay, we climb Lee’s Hill and approach the first of two vineyards. “For a fraction of a second,” says Bantock, “you don’t know if you’re in France, Italy, or the Okanagan.”

As we approach the middle of the island, the soft grasses and open fields give way to native forest. Tall fir and cedar trees line the road. Nearing Ganges, Saltspring’s main town, we catch glimpses of the ocean and offshore islets through the trees.

“You can just barely see the shimmer,” says Bantock. “It’s lovely here to just choose a side road and go down to the water.”

Descending into town, we slow to allow pedestrians to cross near the Saturday Market. We park and follow the crowd into Centennial Park. This is one of the country’s best markets, with some 100 vendors offering local art, crafts, baked goods, fruits, vegetables, and antiques each week.

Overhead, a floatplane drones, and the scent of Thai takeout spices the air. Bantock drifts away while I shop for organic tomatoes, garlic, cheese, and bread. I find him a few stalls away, bartering with an antique dealer for a Victorian photo album.

“I’ll give you $15 for it,” he offers.

“I have $35 on it, but I will fall, fall, fall to $20, for the sake of community,” the vendor replies with a smile.

“Sold,” he says, offering her a bill.

As we walk back to the car, we admire the boats that bob at their berths in the harbour.

“It’s a great mix,” Bantock observes. “There’s everything from crab fishermen’s boats to refurbished tugs, even great yachts, like the one that brought Oprah Winfrey here.”

“You mean the one people say brought Oprah Winfrey here,” I tease. Islanders love to speculate about the celebrities who visit Saltspring or live in our midst. Some have become part of the community, while others are grist for the gossip mill.

“People slip in and out,” he shrugs. “You never really know who’s here.”

As for his own celebrity status, Bantock says Saltspring is pretty laid back. “People tend to accept you for who you are. One of my soccer mates told me that he was asked if he knew Nick Bantock, the famous writer and illustrator. My friend said, ‘No. I play soccer with a Nick Bantock. I don’t know who you’re talkingabout.’”

In fact, Bantock has had many different lives since he was schooled in fine art in England. He has worked at a betting shop in London’s East End, a charitable arts trust, a science-fiction bookstore, a travel agency, a pub, and a poster factory. He trained for a year as a psychotherapist in the late 1970s, then returned to art. Before moving to Canada, he designed literally hundreds of book covers, including ones for American literary icons Philip Roth and John Updike.

“When I came here in 1987, I really wanted to break free, but I didn’t know how,” he says. Then he received a call from a Los Angeles art director, who wanted to work with him on a book.

“I had so many things I wanted to express through books, through text and images. I realized that it was time to work on my own books.”

The resulting Griffin & Sabine series catapulted Bantock onto a world stage. “When the first one came out in 1991, I was living on Bowen Island,” he says. “In a period of two months, I went from complete obscurity to suddenly sitting in front of Katie Couric on the Today show. . . . Living on Bowen was my protection, and in a way, that is what Saltspring also provides. It gives me the ability to keep on creating, as opposed to being distracted.”

While the artist feels safely tucked away on Saltspring, he also appreciates the island’s relative sophistication.

“I just loved it here, from the moment we first came in 2003. I once counted more than 30 cafés and restaurants. There’s this incredible balance between community and choice, which is really, really rare. Plus, it’s exquisitely centred. You can get to Vancouver in half an hour by seaplane.”

Saltspring Island’s natural beauty, and residents’ common commitment to protecting their environment, helps to unify the populace. “People here see themselves as shepherding the land,” says Bantock. Most recently, islanders banded together with The Land Conservancy of B.C. to save the Creekside Rainforest along Cusheon Creek.

“We may fight like cats and dogs over island politics, but when it comes to the truly important things, there’s just that sense of care and community built in here.”

We take Lower Ganges Road out of Ganges, and are pressed to make a choice when we intersect Vesuvius Bay Road: head west to explore the village of Vesuvius, or continue up the island on North End Road.

We choose the latter, passing the Fritz Movie Theatre—its title a tribute to a resident cat that had been named for German director Fritz Lang. The cinema screens first-run films and does its best to please all islanders, young and old.

We follow North End Road past Churchill Farm, a pretty acreage with a colourful market garden. Just beyond Stark Road, St. Mary Lake—the largest freshwater lake in the southern Gulf Islands—comes into full view on the west side of the road. We turn into a small pullout facing the water. Golden light radiates across the lake’s surface as a stiff wind pushes waves firmly to the shore.

“It’s such a lovely, tranquil lake,” says Bantock. “It’s still enough for swimming, but big enough to have a sense of weather on it.” He remembers the first time he saw this lake: “My very first thought was that it was the place of perfect childhood. I imagined a place like this from growing up with The Wind in the Willows.” I, too, am wistful, as the scene evokes my own childhood on the shores of Ontario’s Lake Huron.

Pulling back onto North End Road, we continue our drive to the island’s northern reaches.

“This is the beginning of the female landscape,” says Bantock. “It’s rolling now as opposed to rocky.” As we pass the turnoff for the island’s most northerly point, we laugh at the Saltspringian irony of its name: Southey Point.

North End Road curves around a bucolic sheep farm, then turns southward, becoming Sunset Drive. Here, the gnarled branches of bigleaf maples arch across the road and waist-high ferns fringe its edges.

It’s surprising we haven’t encountered more of the island’s ubiquitous Columbian black-tailed deer today. Though lone black bears and cougars may swim to the island occasionally, Saltspring’s deer have no established predators. They appear everywhere—at the edge of the road, in my front yard, grazing on perennials in Ganges.

“At times, we have deer eating things we don’t want them to eat,” Bantock acknowledges, “but I like the very fact that nature is, to some extent, organizing itself here.”

From Sunset Drive, we branch onto Vesuvius Bay Road. When we come to the next big junction, rather than follow Lower Ganges Road back to Ganges, we take Upper Ganges Road. Bantock slows on this winding, narrow route, banking through its many curves. Old arbutus trees, with their peeling cinnamon bark, bend over the roadway.

“In the early morning and late afternoon, the dappled light through here is just exquisite,” he says. Below us, smoke curls from the chimney of an old farmhouse, and moss covers the cedar shingles of a ramshackle garage.

“It’s almost the perfect halfway house between North America and Europe,” the artist observes. “Two cultures at their best, creating a sense of balance.”

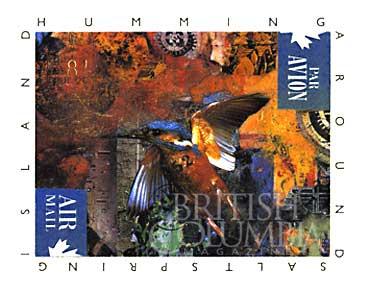

Bantock’s studio gallery, The Forgetting Room, is situated at the end of this road in a new development called Merchant Mews. A stuffed, full-size mountain sheep, sporting an embroidered Turkish skullcap and a Gauguin-inspired necktie, dominates one of the gallery’s front windows.

“That’s Francis,” explains Bantock. “Francis Ulysses Greig.” Bantock spotted the creature in a Vancouver Island taxidermist’s shop. “I went in looking for a stuffed mouse, and came out with Francis,” he laughs. “He’s very good company, and he has proved his weight in gold in attracting the right kind of clientele.”

Eighteen years after the original Griffin & Sabine—and some two dozen books later—Bantock has returned to his first passion: art, which is now his sole focus.

“Coming back to it was like being able to speak English again,” he says. He displays and sells his artwork at the gallery, where iconic pieces from the Griffin & Sabine era hang beside more recent works. In the quiet winter months, he paints and creates his larger collages.

“I never know what they’re going to look like before I start,” he admits. “It’s a matter of taking all the skills you’ve acquired over the years, and then waiting for the piece to tell you what it wants.”

Bantock also teaches collage-art workshops here. His students come to study technique, but the artist sees himself as more of a catalyst.

“Instead of telling people how they should see things, I’m trying to show them that there are other ways of seeing things,” he explains. “Trust the process, that’s what I tell my students.”

That’s something I’ve learned to do today, too, as Bantock and I followed our noses around Saltspring Island. I’ve also learned to slow down, and that it’s okay to lose the map once in a while.

“It’s just a different way of looking at things,” says Bantock, smiling. “It has a magical quality, but it’s not magic. You trust your instincts in certain things. Why not trust them a little more?”

Exploring Nick Bantock’s Saltspring

Getting there

Saltspring (pop. 10,000), off Vancouver Island’s southeast shore, is the largest and most

populated of the southern Gulf Islands. Ganges is the main service centre.

- BC Ferries (www.bcferries.com) offers regular service from Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland.

- Saltspring Air (www.saltspringair.com), Harbour Air (www.harbour-air.com), and Sea Air (www.seaairseaplanes.com) fly to Ganges from Vancouver. Kenmore Air (www.kenmoreair.com) flies from Seattle to Ganges.

To do

- Visit Nick Bantock’s gallery, The Forgetting Room (250-537-0096; www.nickbantock.com) at 18 Merchant Mews, 315 Upper Ganges. Advance booking is required for Bantock’s weekend art workshops.

- Browse the “Bantock Collection” in the Griffin

Room, upstairs at Sabine’s Fine Used Books (250-538-0025; www.sabinesbooks.com), 3101-115 Fulford-Ganges Road. The shop specializes in signed copies of Bantock’s books.

- Strike up a lively conversation with a local by asking whether he/she prefers the official oneword or more commonly used two-word spelling of Saltspring/Salt Spring.

Info

- Salt Spring Island Visitor Centre (250-537-5252; www.saltspringtourism.com), 121 Lower Ganges Road.

- A Guide to Salt Spring Island (www.saltspringisland.org).

- Salt Spring Island Market (www.saltspringmarket.com).

- Salt Spring Studio Tour (www.saltspringstudiotour.com).

- Gulf Islands Online (www.gulfislands.net).

- Tourism Vancouver Island (250-754-3500; www.vancouverisland.travel).