This excerpt from the anthology Tales of B.C., by Daniel Wood, was first published in British Columbia Magazine in Winter 2007. This reprinting stands as a tribute to Daniel, who died in 2021.

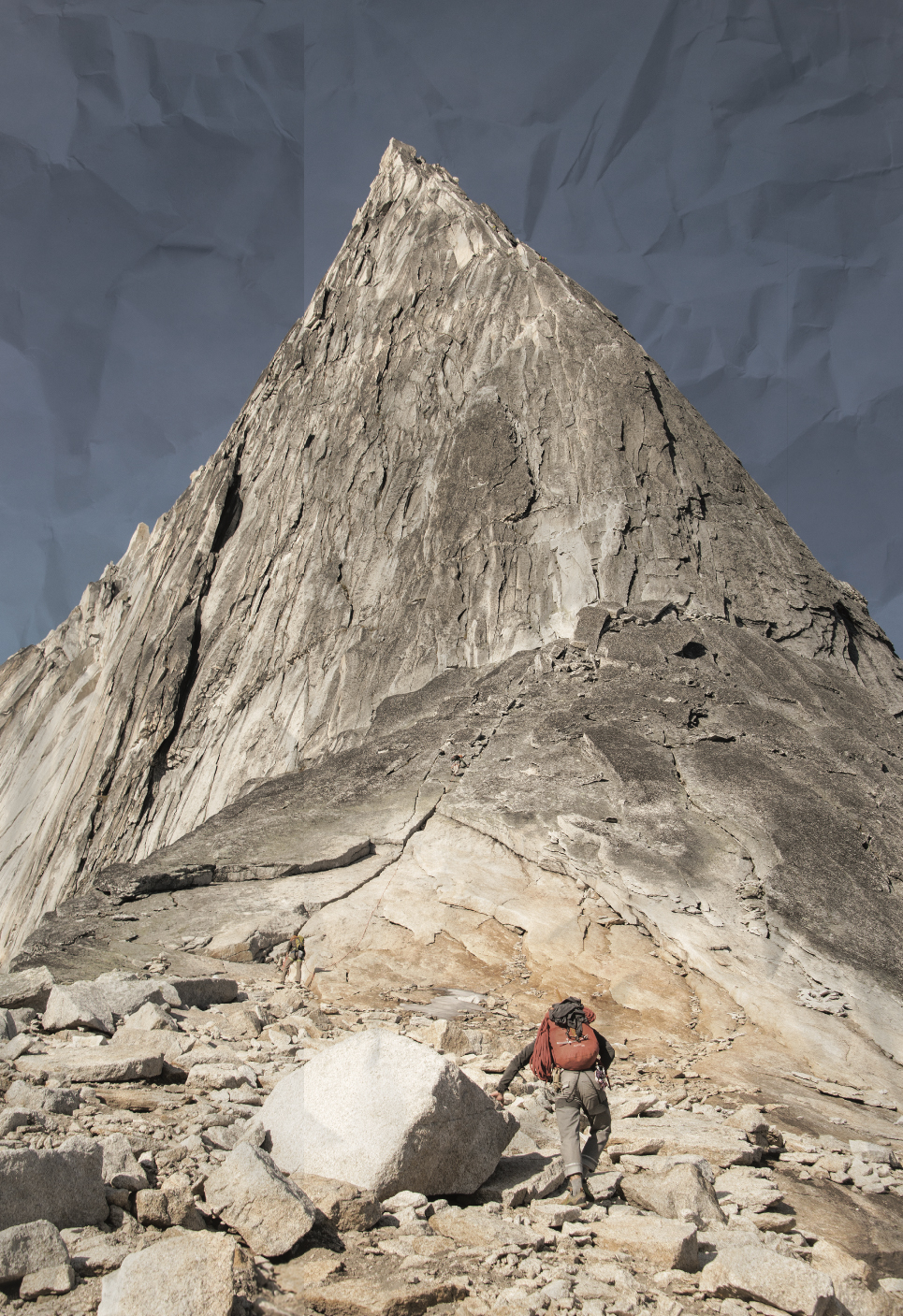

Until that instant, everything was going well—or so 21-year-old Ian Mackinlay thought. The climb from base camp had begun at 6:00 a.m. and, moving along knife-edged ridges and up perilous, near vertical pitches, he and climbing partner Bob Becker, also 21, had reached the 3,176-metre summit of Bugaboo Spire at noon.

The early August sky was cloudless, the view over British Columbia’s Purcell Mountains a panorama of crevice-filled glaciers and massive granite shafts. Few people had ever been where the two men now stood, with half-kilometre cliffs dropping away on every side. Alpinist Rolf Pundt, 41— known for his Tyrolean felt cap with its half-metre long pheasant feather— and Ann “Cricket” Strong, Mackinlay’s agile, 18-year-old Stanford University girlfriend, now appeared, roped together, and joined their friends on the summit.

It was at this moment Mackinlay noticed a line of black clouds approaching from the southwest. This was no time to begin lingering on the summit. The four quickly began rappelling down, descending on ropes toward the infamous gendarme crux—the spire’s most dangerous section.

As the storm moved closer, they sought shelter below the summit in a cave-like rocky overhang. The sky began to roil with mercurial clouds and the air buzzed like a swarm of angry bees. Walls of icy rain struck, followed by pellets of hail and sleet. The hissing sound grew in intensity. Bizarre blue sparks erupted off their heads and the nearby rocks, as if the whole mountain were electrified. And then, in a deafening cannonade, the air around them exploded with a nearby thunderclap and simultaneous lightning flash.

The buzzing stopped momentarily… then, slowly, it began to build again. More fiery blue sparks. Another lightning strike. Then another. Every minute a new one. It began to snow. They knew it would be impossible to descend past the 90-degree pitch of the gendarme in such conditions. A slip there on a slick rock would mean a fall almost twice the height of the Empire State Building.

Unroped and wet, Strong sat at the back of the little cavity between Becker and Mackinlay. Pundt, the most experienced climber, squatted at the sloping entrance, his form silhouetted whenever lightning struck. Within the relative protection of the cave, Strong felt her anxiety start to subside. She wondered aloud to Mackinlay whether he might take a few photographs of the dramatic, squall-engulfed peaks around them. In her hand as she spoke: raisins. In Mackinlay’s hand: a half-eaten salami sandwich.

These are the last things they remember.

Mountain climbers know there are two types of dangers—those you can control and those you can’t. By 1948, the year that most of this story takes place, the Bugaboos had acquired a reputation among alpinists for having some of the most difficult rock climbing in the world. Unlike the Himalayas, which require money, porters, time, and tremendous stamina, the looming and absolutely vertical B.C. spires west of Spillimacheen demand something far simpler: courage. Thus the name, “bugaboo”—an object of obsessive fear or anxiety.

The four climbers on the spire that day were part of a larger group of 18 Sierra Club members visiting the region from California. The trip promised an opportunity for them to test their skills on some of North America’s most challenging rock faces.

By the late 1940s the tale of Conrad Kain’s conquest of the Bugaboo Spire would have been common lore. The famous Austrian alpinist climbed the spire’s precipitous south ridge in August 1916, only to be stymied by a seemingly impossible vertical granite slab blocking his route to the summit—a feature he dubbed gendarme pitch, employing the French word for guard or constable. Kain, unaided, managed to cross this smooth rock face laterally, using only his fingertips and body friction—with nothing but 600 metres of air below. At that time, his conquest was considered one of the most dangerous ascents ever made.

The 18 climbers also knew there were other spires nearby—the Howsers, Snowpatch, and Pigeon—with equally formidable cliffs. They put their trust in the teamwork and expertise they had cultivated on the biggest peaks of the Sierra Nevada.

But the four who ascended Bugaboo Spire on August 4 were not familiar with the area. And the danger they couldn’t control was how these particular B.C. mountains, with their needle-sharp summits, can act as lightning rods when the warm air of the southern Interior meets the colder air of the towering Purcell Mountains. When clouds form and the west winds blow, nature can easily trump experience.

A powerful lightning strike does not dissipate at a mountain’s summit. Instead, its electricity flows over, and through, nearby lower rocks, blasting everything in its path with some 100 million volts and a heat approaching 28,000 degrees celsius—five times hotter than the surface of the sun.

When Mackinlay recovered consciousness from the lightning strike, he was dazed and seemed paralyzed from the neck down. Turning his head, he could make out Strong and Becker sprawled awkwardly within the cave amid the group’s rucksacks and climbing ropes, unconscious. At the cave’s mouth, Pundt writhed in seemingly uncontrollable convulsions. And each spasm on the steeply sloped rock brought him closer to the cliff’s edge, and 600-metre drop beyond.

“Lie still! Lie still!” Mackinlay yelled at Pundt. But nothing he shouted seemed to reach his injured friend’s mind. Unable to move, unable to look away as Pundt thrashed toward the precipice, Mackinlay watched helplessly as Pundt shook with one final paroxysm and tumbled over the edge into oblivion.

When Strong recovered consciousness a few minutes later, she faced calamity. Pundt, the group’s expert alpinist, had just fallen to his death down the west face of Bugaboo Spire. Becker was paralyzed and mumbling incoherently. Mackinlay reported some feeling returning to his legs and right arm. But his left arm didn’t work. For her part, Strong found she could move, but her thinking seemed awfully jumbled—as if her brain’s circuitry had been fried. Of one thing she was certain: below them stretched one of the most fearsome cliffs on Earth.

Mackinlay knew their chances of survival now were very, very slim. Yet, instead of panicking, his thoughts became cold and calculated.

“You’re in mortal danger,” he reflects. “And you need to think—clearly!—how you’ll salvage things. What can you do?”

The storm front appeared to be passing. Bits of blue sky showed. But a new line of black clouds was building to the southwest.

“We’ve got to get out of here,” Mackinlay told Strong. By his estimate, they had less than 30 minutes to escape. But try as they might, they couldn’t rouse Becker, who drifted in and out of consciousness. So, Strong lashed him to the cave’s back wall with one of the climbing ropes, left a rucksack full of food by his elbow, and gathered up the second climbing rope.

It seemed it would be fatal to attempt the route back across the mountain’s vertical west face. They decided to rappel down the near-vertical east face, bypassing the gendarme entirely and letting gravity—in the face of the approaching storm front—accelerate their descent.

It was only then, as Strong took directions from Mackinlay, that she realized how seriously her boyfriend had been injured. His left arm hung virtually useless. She set the rappels herself, realizing he could not, then looped the rope over his right shoulder and fed it into his left hand. He could barely grip it. She knew if he couldn’t hold the rope, he would fall to his death, just as Pundt had.

Mackinlay leaned backward over the edge and felt the rappel rope pull at his shoulder. Sensing the friction within his half-paralyzed hand, he let the rope run for a bit, first a centimetre, then 10 centimetres, then gaining confidence, a metre at a time.

When Mackinlay was about 30 metres below Strong, his feet hit rock. He hollered upward for her to rappel. In a minute, she was beside him, the two seemingly suspended in mid-air on a half-metre-wide ledge—with a cliff now above them and a far bigger one below. They hauled down their rope from its sling, coiled it, and began traversing the ever-narrowing ledge toward the mountain’s south ridge when the second storm struck.

It came as icy wind and sleet. It came as an electrical charge that hummed in the air and reverberated with their bodies. It came as the smell of ozone, a scorched odour like that made by a hot iron on a wet cloth. They hugged the rock face trying to resist the violent buffeting. Mackinlay held out his open hand and sparks erupted from his fingertips. The hissing grew in ferocity until the air exploded with thunder and lightning. At any second, they knew they could be blasted away.

The sleet turned to snow. When they ran out of ledge, Strong fixed the next rappel, wove it around Mackinlay’s body, passed it through his injured hand, and watched him descend 50 metres more toward the icefield far below. Then, she followed his lead. She could feel the electrical current pulsing along the nylon rope, and her hair standing on end. She wondered whether she should even touch the electrified rock face. Then, like a bomb going off, thunder erupted again, and lightning struck a nearby ridge.

Fingers half frozen they fought their way downward—Mackinlay leading and Strong setting rappels. It was only on the very last rappel, when they had reached the seeming safety of the cliffside talus slope, that their rigged rope jammed above them. No amount of tugging would release it. They would have to cross the ice field without it.

They located their ice axes and crampons, which they purposefully had left that morning for their ascent of the rocky spire, and set out—unroped— across the Vowell Glacier as it flows downhill between Bugaboo and Snowpatch spires. Strong told herself she would make it out alive.

She hadn’t taken more than 20 steps on the glaciers sloping surface when she caught one of her crampon’s teeth in the cuff of her trousers. She pitched forward, slid past Mackinlay, and began tumbling down a steep glacial chute. Instinctively she drove her axe into the ice, hoping to halt the fall, but momentum overwhelmed her grip, ripping the climbing gloves and axe from her hands. She slid unimpeded now, gathering momentum, bouncing off rocks embedded in the ice, engulfed in slush and rocky debris that catapulted downhill with her.

“It happened so suddenly,” she recalls.

“I had no time to think. I thought for sure I was going to die.”

From Mackinlay’s vantage point, it certainly looked that way. She was sliding at great speed, her body a tumbling rag doll, arms and legs flailing. Big rocks lay beyond. And worst of all: her trajectory chute was carrying her toward the glacier’s bergschrund, the deep, black crevasse where mountain and glacier meet. If she went into that, Mackinlay knew she would die.

But fate intervened. The path of her fall carried her over a small ice bridge at the chute’s bottom and across the bergschrund. She came to a gradual halt on its far side amid some old avalanche debris. When Mackinlay reached her, her face was bloodied from a forehead gash, but she had no broken bones, despite her 150-metre tumble. Strong looked up at him and smiled. He felt so relieved. Each knew that, without the other, they could not have survived the afternoon’s events.

Trudging through sleet and descending darkness, Strong and Mackinlay staggered into the group’s base camp, exhausted, seven hours after the lightning had struck them. They described what had happened and how they had been forced to abandon Becker. A rescue party was assembled for a nighttime attempt on Bugaboo Spire, while a medic attended to the two injured survivors.

Strong had severe third degree burns on her left leg and shoulder, as well as cuts on her head. Mackinlay, when he tried to remove his clothes, found his metal jacket zipper had been fused closed by the lightning strike and the back of his t-shirt incinerated. The flesh on his back bore a softball sized burn where the current had seared him. His arm was still partially paralyzed. He needed immediate hospitalization, but the unrelenting snowfall made that impossible.

For the next two days, heavy snowfall thwarted all attempts to reach Becker or locate Pundt’s body. On the third day, two members of the Sierra Club group finally reached Becker, still roped within the cave with the rucksack of food beside him. He had probably never regained consciousness. While extricating Becker from the coils that Strong had tied, the two men lost their grip on the frozen body and watched in horror as it slid out of the cave and over the edge where Pundt had fallen earlier.

Mackinlay and Strong spent a few days in hospital in Cranbrook before her parents arrived and drove them to Oregon. They recuperated there for several weeks, waiting for their burns to heal so they could later undergo the necessary plastic surgery.

In time, they went their separate ways. Mackinlay returned to the University of California at Berkeley for his senior year. He graduated as an architect the following spring. Strong continued at Stanford and later transferred to the University of California, where she earned a degree in philosophy.

The bodies of Pundt and Becker were never found—or so people came to believe. The years passed and legend grew about Bugaboo Spire and the two men who’d been hit by lightning on its summit and then vanished into thin air.

In August 1959, while scouting out the mountain’s base for a future attempt of the spire’s unclimbed west face, famed Californian alpinist Ed Cooper sat down against the cliff face to eat his lunch. It was late in the season, and he saw that the melting snow had exposed an old, rotting boot containing a tattered sock. Looking closer, he noticed a pile of bones nearby.

He didn’t realize at that moment that directly above him, 600 metres up, was the cave.

And what became of the two that survived? On August 3, 1951, three years after the accident, Mackinlay received a postcard in Hamburg, Germany, that had been forwarded from place to place as he toured Europe. It was signed “Cricket.”

Cricket! Since their parting, he had expressed the desire to see her again. She seemed disinterested. When he heard she would also be travelling Europe, he suggested they try to meet, but felt little would come of it. Yet, here was her note, advising him she would be picking up mail at the American Express office in Venice, Italy, on August 4 at 11 a.m.

As he studied the note, his eyes kept returning to the date and time. If I drove all night, he thought. He drove all night.

The rest, as they say, is history. Mackinlay was there when Strong entered the American Express Office in Venice. Three days later, he proposed.

Shortly after that, on September 14, the two stood before the Mayor of the Sixth Arrondissement in Paris, France. The man apologized for having left his false teeth at home that day. In a nearly unintelligible Parisian patois, reciting arcane French legalese with no teeth, the mayor read the marriage vows. Every once in a while, he’d look up expectantly and ask, “Oui?” And they would reply, “Oui.” At the end, he had them each sign their names to a form that contained 14 blank spaces below.

“Pourquoi ça?” Mackinlay asked, pointing.

“Pour les enfants,” the mayor replied matter-of-factly. And, he added, they could apply for an additional form if they had more than 14 children. Mackinlay and Strong tried not to giggle.

They had five children. And they continued climbing mountains, drawn by the exhilaration and challenging puzzle of getting to impossibly high places. Both had looked death in the face on that day in August 1948, and they had come to trust that fate, and not fear would direct their lives.

The couple divorced in the early 1970s. They remained connected—bound together first by lightning, then by love and children, and now seven grandchildren. Mackinlay is a practicing architect in the San Francisco area. Strong lives in Berkeley, and works in a university library. They see each other about once a month. They are the best of friends.

Get the Book

With a career spanning five decades, award-winning writer Daniel Wood has inspired, informed, and entertained generations of readers. Whether he’s exploring human nature, scientific discoveries, oddities, or environmental wonders, at the centre of these stories are people, their ideas, and their dreams.

This one-of-a-kind anthology features 28 of Wood’s best magazine articles including a near-death hot air balloon ride, BC’s pot-growing pioneers, Elvis impersonators in the Okanagan, the province’s first dino-dig, and its last free-range cowboys. Get this compelling collection of BC tales at a bookstore near you or order online at bcmag.ca/talesofbc.