In early July of 1791, during a first European exploration of the Salish Sea, Spanish naval officer José María Narváez piloted his 10-metre schooner, Santa Saturnina, north through the Strait of Georgia past a large delta. Tacking far offshore to avoid sandbars and cross-currents from the debouching river (that would be the Fraser), he anchored off what would come to be known as Point Grey, where Musqueam canoes soon arrived, eager to trade. Departing, he entered Burrard Inlet, the harbour around which the city of Vancouver would eventually coalesce, but journeyed only as far as English Bay. Resuming his northward trek, he picked his way through a scatter of islands occupying an even larger break in the mountainous shoreline palisade. Eschewing the exploration of another inlet in favour of going ashore on the Sunshine Coast, he nevertheless must have liked what he’d seen, inking it in as Bocas del Carmelo—“mouths of abundance”—on his chart.

The following summer, intrepid British explorer Captain George Vancouver would survey the Bocas, discovering how its islands occupied a funnel-shaped area (the virtual definition of “Sound” to British navigators) before narrowing to a lengthy fjord. With typical colonial hubris he named it Howe Sound after fellow naval officer Richard Scrope, aka Lord Admiral Earl Howe. Travelling, as they did, the same time of year, both he and Narváez might have seen grey or humpback whales surfacing, orcas chasing chinook salmon, dolphins or seals, rock islets coated in lazing sea lions, sea otters floating on kelp mats, and everywhere scarlet lines of sockeye salmon ribboning into coastal rivers to spawn—a plentitude that neither could have imagined would be wiped out in a century, then take another hundred years to even begin to recover.

Of course, none of what Europeans “discovered” about Howe Sound was news to the Squamish or Sechelt First Nations whose villages flourished on its shores and islands since time immemorial; both groups, unfortunately, would have front-row seats as the new arrivals laid incremental waste to the ecosystem on which they’d so long subsisted. Though Howe Sound would lose most of its iconic mega-fauna to overhunting, overfishing and the food-chain ravages of industrial pollution as nearby Vancouver grew, it would nevertheless remain relatively wild for such a near-urban enclave. The fact that it’s still a place of fragile abundance and teetering beauty underscores the need for everyone who now depends on it to work together to protect and enjoy its wonders in a sustainable manner—the very reason behind its September 2021 designation as the Átl’ḵa7tsem/Howe Sound UNESCO World Biosphere Region.

Whenever I make the drive home to Whistler after being away, I always feel I’m back in the hood when I see Howe Sound—even though I’ve still got over 100 kilometres to go. It’s testament to the self-identity and connectivity of the broader Sea to Sky Region that runs from Horseshoe Bay to Pemberton with Highway 99 as an axis, as well the ecological cohesion of watersheds that empty into Howe Sound—which form the borders of the new biosphere region. I’ve contemplated this majestic indentation in the coast on occasions too many to recall, even beginning a recent book with a description of a blue-sky, springtime trip along the road that shadows it, describing the waters below shimmering “like a clinquant carpet.”

But even if I appreciated Howe Sound’s aesthetic contributions from my very first visit, I didn’t know much about it. Like many who live here, I clued into the reality of its human charms, natural riches—and vulnerability—in bits and pieces over time: a trip to Gambier Island and a feast of locally caught spot prawns and crab; ferry rides to the funky peri-urban community of Bowen Island where my partner lived for a while; making annual mental notes of accumulating clear-cuts and powerlines blossoming across the upper reaches of its mountainous flanks; hearing about, then joining protests over an ill-advised LNG terminal; reading for years of expensive environmental clean-ups in the sound, then silently rejoicing when reports of whales and dolphins returning to rejuvenated waters surfaced (pardon the pun), thinking it money well spent.

Recently, working with geologist Dr. Steve Quane of the Fire & Ice Aspiring Geopark project, another potential UNESCO designation for the Sea to Sky that would overlap part of the biosphere region, I’ve learned about the sound’s physical character—how it was carved by a lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet during the height of the last Pleistocene glaciation; how the Porteau Cove Sill, crossing its waters some 30 metres below the surface, represents the terminal moraine of that glacier; how the copper mine at Britannia Beach was once the largest and most innovative in the British Commonwealth; how a scatter of remnant volcanic vents can still be found along the sound’s northern reaches; and how the Stawamus Chief, a granitic pluton formed some 20 kilometres below the Earth’s surface during the Cretaceous, was eventually exposed—much to the delight of hikers and the international rock-climbing community—through the dual processes of tectonic uplift and downward erosion.

What these myriad vignettes add up to is a portrait of a living, working and evolving landscape—an intersection of natural and human values that need to be reconciled at every turn. Getting everyone at the table and on the same page with this ideologically simple yet functionally tedious task is what a biosphere region is all about.

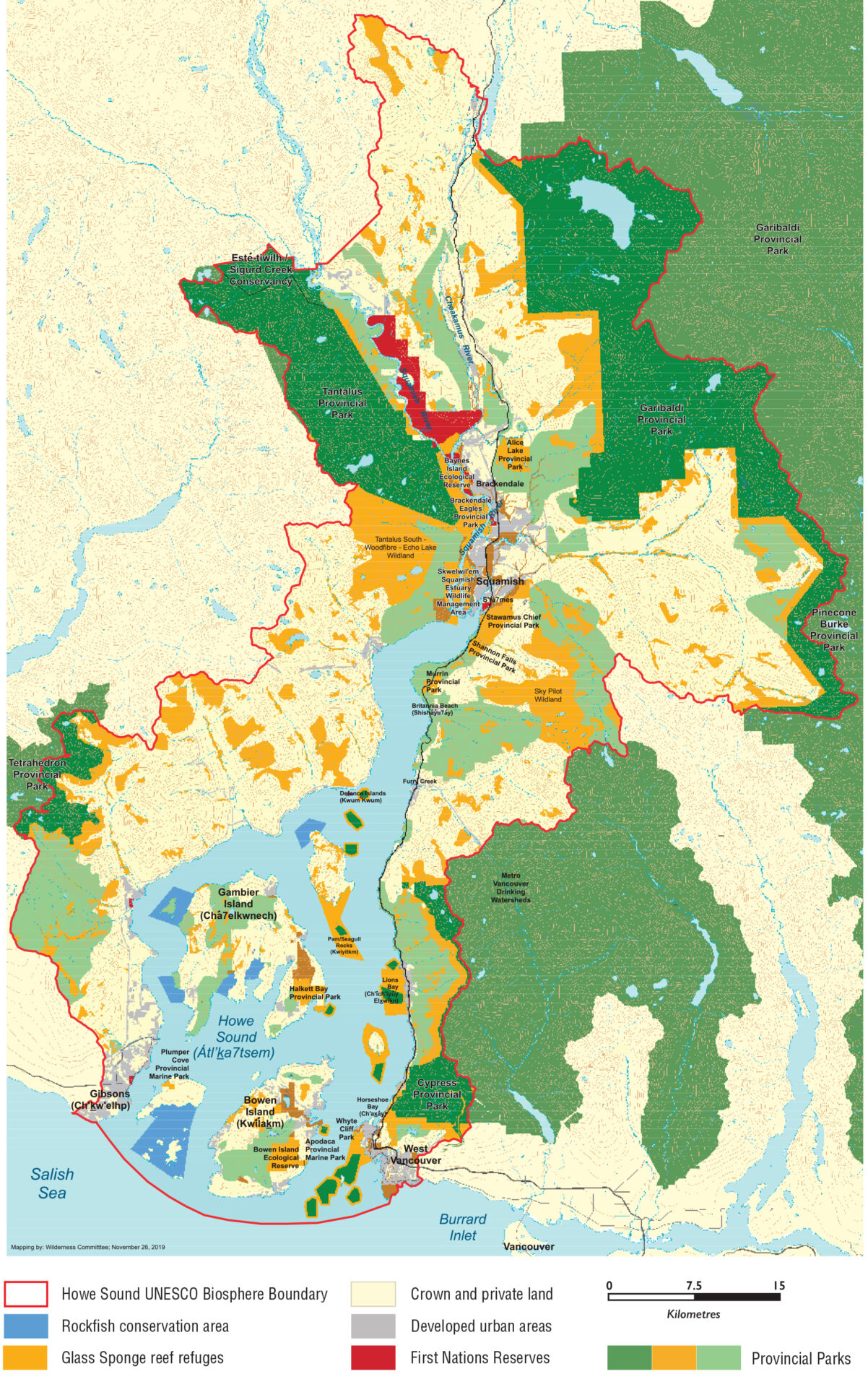

Biosphere itself is a word easily defined—that part of the atmosphere and Earth’s surface occupied by living organisms. As such, the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves (Átl’ḵa7tsem / Howe Sound chose to use “Region” instead of “Reserve” because of the fraught history of the latter in Canada) comprises 727 internationally designated areas in 131 countries that demonstrate a balanced relationship between all living organisms (i.e., people and nature) on those landscapes. Created under the Man and Biosphere Programme that also includes UNESCO World Heritage Sites and UNESCO Global Geoparks, Biosphere Reserves are, at their essence, learning areas that provide local solutions to the global challenge of harmonizing the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use. The designation doesn’t mandate anything, usurp lands or titles, or interfere with development; instead, it’s a conceptual entreat—a semiotic for all stakeholders to work together. This takes place across the interfaces of three subdivisions within each designation: strictly protected core areas like provincial parks, ecological reserves, conservancies and marine refuges that contribute to the conservation of landscapes, ecosystems, species and genetic variation; buffer zones surrounding or adjoining core areas that are used for activities compatible with sound ecological practices that can reinforce scientific research, monitoring, training and education; and unprotected transition areas where communities foster socioculturally and ecologically sustainable economic and human activities.

“What I liked right away about the concept was that it didn’t take anything away from anybody,” says Bob Turner, a retired geologist and two-term mayor of Bowen Island. Long involved with initiatives to protect Howe Sound, he’d watched an earlier attempt at creating a national park go down in flames. “There was a lot of resistance because people felt there was too much to lose. But this is different—it’s aspirational, there are no losers.”

“We’re not another bureaucracy or hoop people need to jump through, but more of a regional conscience—a showcase for best practices around the entire watershed,” says Ruth Simons, who shepherded the initiative to successful completion over a five-year period.

Simons’ journey started earlier, however, through her advocating for a holistic, comprehensive land and marine use plan with the Future of Howe Sound Society in 2012. By 2014 she was organizing and hosting the Howe Sound Community Forum, meeting twice a year with stakeholders and different levels of government, including First Nations. Although there was plenty for the parties to address and seek cooperation around, talk often turned to finding a way to protect Howe Sound. Although BC Spaces for Nature had previously suggested the UNESCO route and it hadn’t gone anywhere, Simons had an epiphany moment that saw her circle back to the idea. “I was visiting Tofino in 2016 and went into the Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Region office and talked to some staff. I learned about the framework of a biosphere region and its mandate, and it made a lot of sense to me.”

Rounding up a clutch of Howe Sound’ers including Turner, she returned to Clayoquot on a field trip. More people got interested, and more road trips were made. The decision to move forward included a fundamental difference from the original suggestion—looking beyond the marine environment to the entire watershed. By 2017, the Howe Sound Biosphere Region Initiative, with Simons at its helm, had settled on boundaries and was exploring the possibility at community forums and with First Nations, garnering support anywhere it could. “Anyone interested would be invited to help and we’d send them away with a task,” recalls Simons. “So, it was really a grassroots effort done on very little budget—most of the work was in-kind.” By December 2019, they’d delivered a draft of their 370-page application to the Canadian Committee on UNESCO in Ottawa. Feedback from reviewers amounted to several more months of work with a final document submitted in July 2020. Review by an international advisory committee recommended it for approval. The recommendation was accepted by UNESCO in September 2021, and, in true pandemic fashion, Simons and team got the word over Zoom.

Although a mild media feeding-frenzy ensued, the outcome, as is often the case with something large and unwieldly, was mixed: people were happy about the existence of the Átl’ḵa7tsem/Howe Sound UNESCO Biosphere Region and thought it was cool, but had no idea what it meant. And many others hadn’t heard about it at all. Which made explaining it difficult. Because a conceptual designation doesn’t prohibit or commandeer anything, what exactly will happen? What changes, if any, will people see in the region?

“An economic shift over the past few decades toward tourism and recreation has seen many more people visiting the region, putting pressure on every aspect from its communities to ecosystems,” sums Simons. “So, for instance, going forward there will be more emphasis on ensuring that we’re conserving and protecting sensitive ecological areas and habitat so we don’t suffer any more biodiversity loss.”

For his part, Turner is hopeful of awareness building on the astonishment factor. “It’s a pretty wild place but not isolated up along the mid-coast where only the very affluent or very hardy can access it,” he begins. “It’s right around the corner from Vancouver, delivering a slice of coastal BC to 2.5 million people in a remarkably raw form. So, the inspirational, aspirational and educational potential of Howe Sound actually exceeds similar-but-more-remote places. Along with coastal ecosystems, there’s 20th century discoveries like glass sponge reefs. And from a biodiversity point of view, it truly is ‘Sea-to-Sky.’ The extreme relief puts a lot in a compact area; you can climb up into the alpine right from the ocean’s edge.”

You also can’t underestimate the power and motivation of community pride that comes when your home turf is recognized worldwide as a special place. “I see that from the folks on Bowen who hope this an opportunity to think a little bolder and more imaginatively,” says Turner. “A chance to do things better, to ‘up our game’ on sustainability, biodiversity and conservation initiatives, as well as relationships with First Nations.”

Turner believes a knock-on-effect on visitors from afar is probably a decade out, but that the next five years will be crucial. With expectations high, there’ll be a need to meet some. “I’m part of a conservation caucus for the biosphere region, and it’s interesting to reflect on our meetings now versus before, with the new commitment to a geography, a bigger common cause. How that might play out is hard to know, but I’m hoping it’s a reflection of a whole new paradigm.”

Jessica Shultz is a PhD candidate in marine biodiversity at Ontario’s University of Guelph and an advisor and marine ambassador to the biosphere region. She outlines some the strong biological arguments for protecting Howe Sound. “Over 700 species of marine animals live there. That’s representative of other coastal areas but the biosphere region is one way we can call attention to them. Relatively speaking, it’s easier to take care of more remote wildernesses, so the fact that this one’s used for activities from industrial to recreational to food harvesting makes managing threats to its integrity a huge task. The work that needs to be done is finding a sustainable approach to all of these.”

Underpinning the sound’s biodiversity are its several special habitats. “These waters are important for forage fish like herring and anchovy that feed whales and salmon. Eelgrass beds offer important nursery habitat for salmon and rockfish; they also provide a storm buffer and are important for climate change because they’re so efficient at transferring carbon into the sediments,” says Schultz. “And the 18 or so glass sponge reefs that have now been discovered? Well, they’re a cornerstone for conservation and biological diversity, creating habitat for other creatures.”

As it turns out, glass sponge reefs require two things to get started: bottom areas of low sedimentation—like the kind of towering substrates plowed up by glaciers on the bottom of the sound; and high levels of dissolved silica—the kind an abundance of upstream rock from the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt delivers to these waters daily. How’s that for tying mountains, watersheds and ocean biodiversity up in a bow?

From the biological standpoint, Schultz’s hope is that people understand that they’re not separate from nature, that we’re all part of the same ecosystem, the same spectrum of biodiversity. “Interconnectedness is an important message to get across. We’re not in conflict with the economy. When we have sustainable development, where nature and biodiversity and ecosystems are thriving, it’s quite the opposite. The biosphere region will help reinforce this—instead of just the idea, we’ll have a framework for doing things better.”

An example is the Searching for Slhawt’ (Herring) Program, a partnership between the Marine Stewardship Initiative and local groups, led by youth from the Squamish Nation. The project recently raised almost $20,000 through the West Vancouver Foundation’s Give Where You Live campaign to study where and when herring spawn in the sound, how well eggs survive in different locations, and the cultural and social importance of the species to the Squamish people—all in the service of advancing Indigenous stewardship of this critical resource.

Unlike Narváez and Vancouver before him, Captain George Henry Richards of the HMS Plumper, who surveyed Howe Sound from 1859 to 1860, naming (or renaming) many of its islands and mountains didn’t think much of the place: “Howe Sound… is an extensive though probably useless sheet of water, the general depth being very great, while there are but few anchorages,” he reported. “It is almost entirely hemmed in by rugged and precipitous mountains rising abruptly from the water’s edge… there is no available land for the settler, and although a river of considerable size, the Squawmisht, navigable for boats, falls into its head, it leads by no useful or even practicable route into the interior of the country.”

Nothing could have been more dismissive and short-sighted of the land that the town of Squamish would eventually occupy. We humans cannot separate ourselves from nature, yet we contribute to nature’s overall diversity through our own variability and adaptability. The final piece of the biosphere region, in fact, lies in its cultural constellation of coastal communities. Large or small, but mostly discrete with their own unique personalities, Turner refers to them as “little ideas factories.” Places that come up with their own innovations on how to live better on the land. “Each community brings something to the table,” says Turner. “But the shared waters tie us together—it’s a good melting pot.”

Joyce Williams, Squamish Nation Co-Chair of the Átl’ḵa7tsem /Howe Sound UNESCO Biosphere Region expresses hope that the designation brings these communities together for effective decision-making, building connection to the territory and the land, helping people “better honour and respect the environment” and the life contained within it. As much as it’s about sustainable development, she notes, “Átl’ḵa7tsem is really about beauty and hope.”