In the early evening darkness of September 13, 1987, the 15-metre fish packer Supreme No. 1 tied up in Ladner Slough for the offloading of its illicit cargo: 10 tonnes of Thai marijuana. BC’s Earle McPhee* had signed onto the operation only a few hours before, risking jail-time for the promise of significant payment for helping unload the boat. The front-page headline in The Vancouver Sun the following day read: “12 face charges in Delta drug bust.”

With a street value of $40 million, the article explained, the bust was one of the largest in BC history. I didn’t need to read the article; I’d already heard what had happened. That’s because McPhee and several of the others arrested were my friends—with connections that went back to the late ’60s.

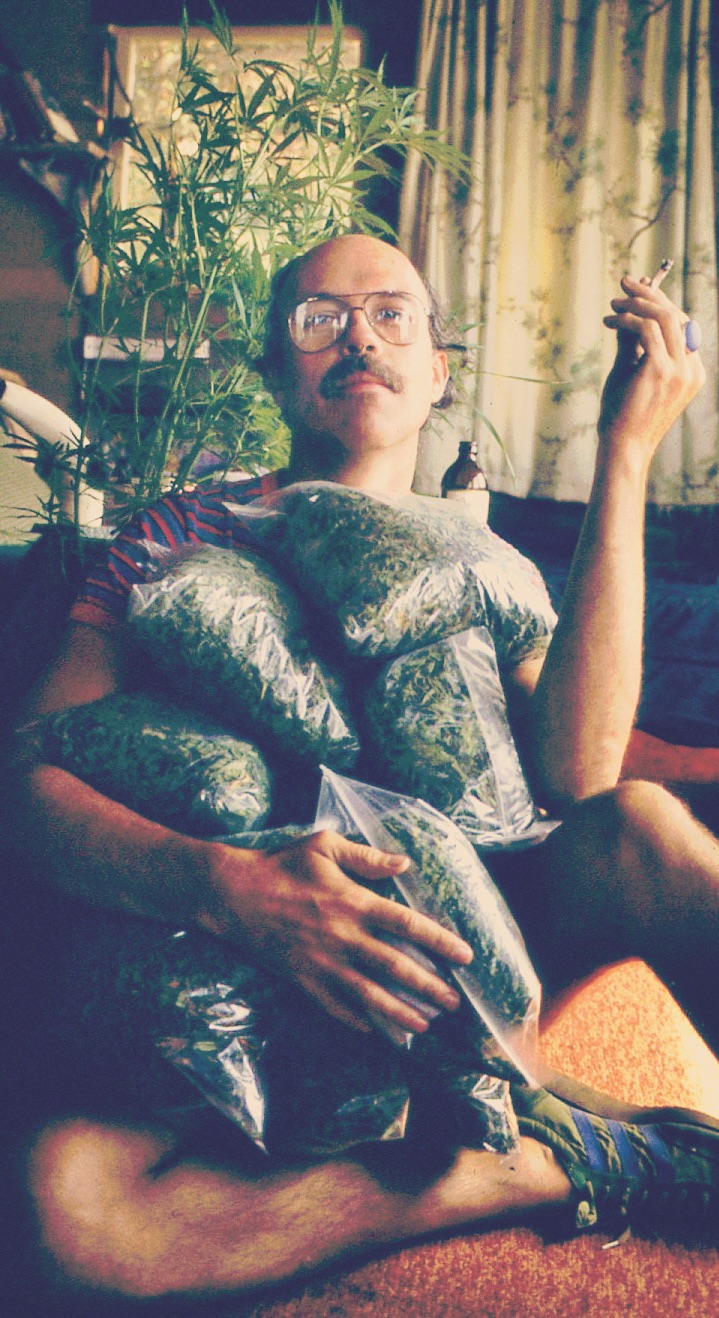

In the 50 years between then and now, some of the BC people I knew when the Lotusland myth was first established went on to create outdoor marijuana plantations called Guerilla Gardens. In the ’70s, there wasn’t a rural town from Lasqueti Island to Kaslo (and myriad places in between) where a pickup truck with a water tank in the bed didn’t hint at devious backcountry agriculture. In the ’80s, these friends went on to develop more lucrative grow-op franchises, sharing the profits from potent sinsemilla indoor operations between the tenant-farmer, who took the risk, and the franchiser, who’d fund 10 or 20 basement installations. By the ’90s, some went fully professional (and got extraordinarily rich) developing the powerful strains of exportable BC Bud of the past 25 years.

In the earliest years of Lotusland, a young street lawyer named Mike Harcourt defended more than a few of those busted by Vancouver’s infamous narcotics officer, Sergeant Abe Snidanko, the nemesis of the hirsute and giggly.

Harcourt today admits to a certain irony that, as the former Premier of British Columbia, he’s currently Chairman of the Board of True Leaf Medicine. In this capacity, he’s involved—now that Canada is about to legalize it—in producing 15 million grams of medical marijuana in the company’s soon-to-be-completed Lumby, BC, facility. “It was a waste of police time. A waste of money. And foolish public policy,” he says of Canada’s 95-year-long prohibition against marijuana.

In 1972, more than 1,000 Canadians a month were being convicted for marijuana infractions. Many went to jail for mere possession. This was especially true in Vancouver where the “drugs, sex, and rock ‘n’ roll” mantra resonated loudest and where dozens of communal houses in the Kitsilano area were known to be places where a whispered word could produce a $15 lid of weed (not to mention the availability of hashish, LSD, mescaline and psilocybin mushrooms). The police played a losing game of Whac-A-Mole against these drug houses at that time, but luckily, they never came to 1148 West 7th Avenue, where I lived. (The house is no longer there.)

McPhee, now 72, remembers one of the house’s residents unpacking a box with the shipping label reading “Push-up bras: 38-C.” There were, indeed, bras inside. But the push-up crescents were formed from precisely-molded hashish. He remembers evenings spent listening to Creedence Clearwater amid the smoke of an ever-moving joint. And then there was the afternoon that several police cars pulled up, and amid frantic shouting, the 1148 inhabitants flushed their personal pot stashes down the toilet, only to learn seconds later it was the house across the street that was the target of Snidanko and his detectives.

When the police did appear years later during the 1987 Supreme No. 1 bust, McPhee and two others dove overboard in an effort to escape. He surfaced to face a police pistol and a RCMP officer inviting him to swim to the muddy Ladner shore. He obliged. And spent a year in jail. Sobered by this—and the subsequent loss of his marriage—he went straight. But a few 1148 friends, propelled by the existential thrill of trying to elude authorities, took a different direction.

John Sinclair* was one of those who saw himself as an outlaw. Risk was his addiction. At 1148, I watched him pick up a bulging Safeway bag he’d recently deposited on a wet kitchen counter only to have the bottom fall out. Amid jaw-dropping expressions from those there, $15,000 in tight-rolled, elastic-bound bills hit the floor. His pot profits, he announced. And declined sarcastic offers to help him pick it all up. Provoked by my curiosity over the sources of his seemingly-endless supply of marijuana, he took me on a road trip to rural Gillies Bay on Texada Island in 1981 to see his friends’ Guerilla Garden. On an obscure, sunny, south-facing slope, Sinclair’s buddies had run a hose-line along an indistinct trail, fenced a clearing against deer, and planted seedlings. When we arrived in late June, I found myself standing in the middle of the scrub-enclosed plantation where—as bright as emerald—hundreds of thigh-high marijuana plants stood. It was, Sinclair estimated, one of tens of thousands of Guerilla Gardens in the province as hippie back-to-the-landers found a way to support themselves amid the BC wilderness.

Later, I recall standing in downtown Nelson, talking with a leading municipal official, asking him—with the mills closing—what sustained the city’s economy. I watched as he extended his arm upward toward the surrounding Selkirk Range, turned a 360-degree circle, and said simply: “Marijuana.” We both laughed. It is not an exaggeration, I suspect, that much of rural BC—in the years bracketing the Millennium—depended on the widespread cultivation of pot.

During the decade of the rural Guerilla Gardens in the 1980s, the outdoor entrepreneurs learned that if they removed every single male from the plantation, the unfertilized females would go… well, BERSERK! Their buds would swell and produce huge amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), hoping to attract male pollen. The growers speculated that if they could produce pretty-high THC sinsemilla (seedless) pot outdoors, cross-breeding the best female plants with potent Afghani and Thai strains, what would happen if they cultivated their hybrid species of pot in indoor grow-ops? Under perfect conditions. And away from prying eyes. It didn’t take long to learn that they could produce pot 10-times as powerful as the ’70s “doesn’t-get-a-fly-high” Mexican weed of their youth. By the early-1990s, authorities estimated there were 17,000 of these marijuana grow-ops in BC, annually producing 2,000 tonnes of pot.

The exterior of the ordinary bungalow in the 100-block of Vancouver’s West 44th Ave revealed nothing unusual. I knocked and was greeted by an old friend, Sarah Cherney*, then 46, the former matriarch of the 1148 house in the ’70s, and still, in 1992, willing to risk prison for what her basement contained. I descended the cellar stairs behind her. She opened a door. And my eyes were cauterized by an atomic blast of incredible white light. I shaded my face as if confronting God. Ahead of me were six suspended, 1,000-watt, metal halide lamps, and beneath them an equally astounding wall-to-wall garden of chartreuse-green, metre-high marijuana plants, their mouse-sized, THC-packed female buds trembling under the slow oscillation of fans.

“My girls! My virgins!” Cherney said of her 150 or so treasured, sinsemilla step-daughters. “Boys aren’t allowed,” she teased, as she waved a cautionary finger toward me.

We sat for a while on two overturned barrels and she regaled me with details from the film The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie—a story about hormones and the hazards of an all-girls school. I wondered if my hormones—or neurons—were reacting to the all-female juices in the air. Cherney picked a nearby bud with feathery red and cream pistils sprouting from its surface. “For you,” she said. In three harvests annually, this basement grow-op would produce $150,000 in revenue, a third to Cherney, and the rest to the investor/franchiser who had a dozen other rental houses with clandestine plantations inside.

So as the early ’90s passed, the stage was set for BC Bud and a multi-billion-dollar marijuana industry.

Many of the lessons acquired from the breeding of the increasingly potent BC Bud fed the fever—and incomes—of tens of thousands of marijuana growers in the province. Hybridization, cloning, controlled indoor lighting and watering systems, skunky-smelling sinsemilla buds… and before long the word was out: BC Bud was the most potent dope in North America. THC levels were, in some cases, at 25 percent. It could send your brain into orbit. It could do the same to your bank account. Top quality Bud sold for $3,000 a pound in the US. Soon, there were guys carrying loaded backpacks across the border, and southbound helicopter-loads and people hitting BC Bud-packed tennis balls into Washington. It was a smuggling free-for-all, much as happened almost a century ago when Canadians supplied the US with alcohol during prohibition. (A friend of mine once attached a big, waterproof bag of marijuana to a driftwood log and snorkelled the Similkameen River south until he was safely in Washington.)

But it didn’t always go well. The Kootenay smugglers with the helicopters got caught while landing $14 million-worth of primo BC Bud in eastern Washington. A massive grow-op outside Bridge Lake, BC, was found to have 23 greenhouses with 15,000 plants, worth millions. Two men lugging 34 kilograms each of Bud in their backpacks—worth $750,000—got caught trying to cross the border near Sumas. By tunnel, by drone, by snowshoes, by airdrop, by hollowed-out log and by rowboat, marijuana exporters tried—and occasionally failed—to bring BC Bud to the lucrative American market.

Then, starting 20 years ago, governments permitted the use of marijuana for medical purposes, and what began as a minor breach in the War on Pot became, in the past few years, a flood. Legalization for medical use and/or decriminalization for recreational use now applies to 28 American states, plus, of course, all of Canada come October. The consequences of this are varied, and sometimes comic. With legalization, the Marijuana Party of Canada is roadkill. The value of BC Bud has dropped precipitously. And thousands of those previously employed in illegal bud production face unemployment.

But here’s the comic upside: An entire new industry is appearing across Canada as licensed marijuana producers and retailers find opportunities to ride the THC tidal wave. By 2023, it’s predicted marijuana will be a $23 billion-a-year industry in Canada, employing over 100,000 people, and contributing billions in taxes to the country’s economy. Goodbye sanctimony! Hello capitalism!

Recognizing the demands of this new industry, Kwantlen Polytechnic University’s David Purcell and his BC associates have designed a series of three $1,500 courses that prepare students to deal with the regulations, production and marketing of marijuana. Over 1,500 have taken these courses and are now finding work in facilities like the 1.3 million square-foot BC Tweed greenhouse in Aldergrove where 250 workers are employed tending and harvesting legal bud.

Dressed for Health Canada reasons in a plastic jumpsuit, booties and hair-net—and looking like an escapee from a really bad Japanese space-invaders film—I joined a few of the equally-garbed workers within BC Tweed’s humungous Aldergrove marijuana farm. And found myself looking at 100,000, chin-high, hydroponically-fed marijuana plants—growing in a single, enclosed greenhouse the size of 20 football fields. When I asked Aldergrove’s Victor Krahn, the former green pepper farmer who actually owns the greenhouse and leases it to Canopy Growth Corporation as a marijuana grow-op, why he moved into farming marijuana, his answer was simple: “Marijuana’s more profitable.” For one thing, he explained: He doesn’t have to compete with Californian green pepper farmers anymore. Secondly: American pot cannot be imported. Third: He therefore has a protected market of 225,000 registered Canadian medical marijuana users; plus several million Canadian recreational users. Come mid-summer of 2018, Krahn’s THC-packed buds would be harvested, he told me, and the leaves disposed of—like the piles of trim already filling the giant blue tubs that line the greenhouse’s aisles.

“Disposed of? Where’s all this going?” I asked, trying to sound not-too-curious.

He declined to say.

I began to speculate aloud on the possibility of hijackers commandeering a future truckload of incinerator-bound trim (as the less-powerful leaves are called) but thought better of it. Having a massive Aldergrove marijuana farm—with all the perimeter security that that entails—is worry enough.

Lumby (population 1,700) lies in the foothills of the Monashee Range and shares with nearby towns certain, odd similarities. In the 1990s, all five of Lumby’s mills shut down, putting hundreds out of work. Downtown stores were boarded up. The tax-base shrivelled. Lumby’s economy became increasingly dependent on the high-value BC Bud produced in the region’s numerous illegal grow-ops. In 2014, when entrepreneur Darcy Bomford arrived in Mayor Kevin Acton’s Lumby office and told him he wanted to build a facility to produce marijuana in town, Acton listened. He was no stranger to home-grown pot. Marijuana meant money. Like Lumby, nearby Cherryville, Nakusp and Edgewood were places ’70s hippies had settled and began breeding what would become BC Bud. Edgewood, Acton joked, was an anagram for “Good Weed.”

In 2017, with $14 million raised via crowdfunding, with 16 hectares purchased, and with former Premier Mike Harcourt serving as chairman of the board, True Leaf Medicine began construction of their Lumby property. Bomford’s goal is to produce 10,000 kilograms of high-grade, medical marijuana annually, inevitably utilizing the skills of local people who cultivated BC Bud during their days as outlaw farmers.

Harcourt said of his current involvement with True Leaf, “These plants have been available to people for thousands of years. They’ve been part of indigenous medical and recreational practises forever.” As a man who famously fell off a Pender Island cliff in 2002 and broke his neck, Harcourt has often found himself listening to others who testify that the best medication against pain is marijuana. It is also a good substitute for those caught in chronic heroin use.

Plus, it makes people giggle. On August 7, 1971—at the height of Vancouver hippiedom—a marijuana Smoke-In took place in Gastown to bring attention to the vigorous anti-pot actions of Vancouver authorities. What began as a peaceful demonstration quickly turned into a riot—with scores of protesters beaten by baton-wielding, horse-mounted police. Over 100 were arrested. Compare that to what happened at Vancouver’s Sunset Beach on April 20 this year (also known as 4/20, a worldwide day to celebrate weed). As the countdown toward 4:20 p.m. was being made, those gathered were reminded to share their joints with neighbours. At that precise minute and hour, an estimated 50,000 people lit up, drew a deep in-breath, and simultaneously exhaled. A cloud of marijuana smoke slowly rose above the Vancouver crowd. People laughed and cheered. A few police officers nearby looked bored. The times had, indeed, changed. For Canada, it marked the symbolic end of almost a century’s prohibition against getting high.

Marijuana in BC:

Just the Facts, Ma’am

-An estimated 2.3 million Canadians use marijuana regularly. Forty percent of Canadians have smoked pot.

-The enforcement of marijuana laws—pre-2018—cost Canada $500 million per year.

-Prior to legalization, there were an estimated 17,000 illegal grow-ops in BC. Over 75 percent of BC Bud was shipped to the US.

-At its production peak, BC Bud was estimated to be worth $7 billion annually. At that time, 74 percent of British Columbians favoured decriminalization of pot.

-There are now scores of licensed marijuana producers in Canada, including at least 22 in BC. BC Tweed’s greenhouses in Aldergrove and Delta contain 230,000 pot plants.

-Vancouver has 147 marijuana stores, providing both medical and recreational pot.

-The 2018 price for a high-quality ounce varies between $78 in Kelowna to $156 in Vancouver.

-The popularity of indica, sativa and hybrid marijuana strains splits fairly evenly: one-third each.