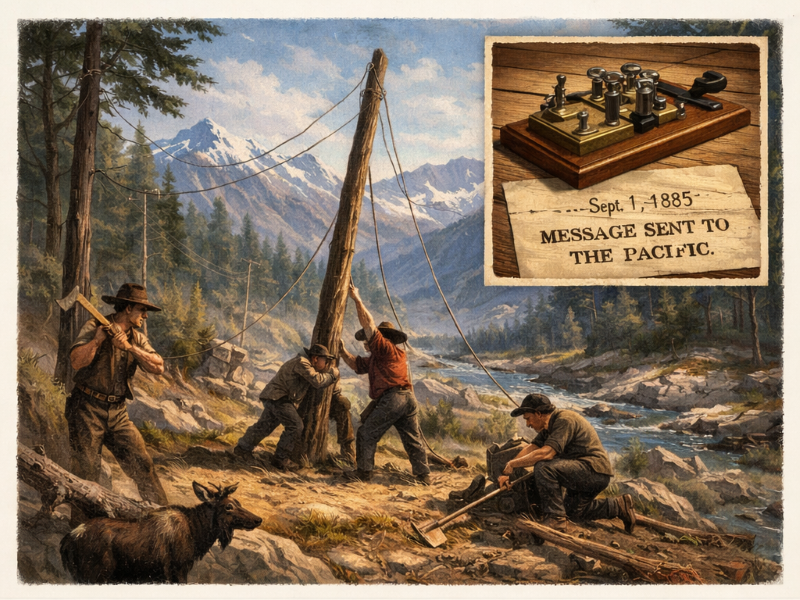

On Sept. 1, 1885, commercial telegraph service was extended “from Montreal to the Pacific,” linking British Columbia to the country’s growing communications network in a way that was immediate, practical – and profoundly nation-shaping.

It’s an anniversary that’s easy to overlook in an age of instant everything, but the first trans-Canadian telegram era marked a real change in how BC related to the rest of Canada: not as a distant outpost connected by ship schedules and seasonal roads, but as a place that could send and receive urgent information in minutes or hours instead of weeks.

Before The “Sea-To-Sea” Wire, BC Was Already A Telegraph Frontier

British Columbia didn’t wait for Confederation – or the railway – to experiment with long-distance communication. By the 1860s, colonial leaders were actively pursuing telegraph lines as tools of governance, trade and security. Legislation from the Colony of British Columbia explicitly backed the construction of telegraph lines and granted rights-of-way, reflecting how strategic the technology already seemed on the Pacific coast.

And BC’s geography made telegraph building a kind of epic: stringing wire through coastal rainforest, across river valleys, over mountain passes, and into boom-and-bust towns that could empty as quickly as they filled. One of the most ambitious projects was tied to the dream of a global line: the Collins Overland Telegraph, intended to connect North America to Europe via Alaska and Siberia. The scheme ultimately failed after the first successful transatlantic cable, but it left a physical and historical imprint across the northwest – including northern British Columbia.

The CPR’s “Shadow Network” Beside The Rails

What changed in the 1880s was scale – and permanence. As the Canadian Pacific Railway pushed west, it erected telegraph wires parallel to the tracks for train dispatching and operational control. That detail matters because it explains why the telegraph could be extended so quickly into public service: the railway needed the line anyway, and once it existed, it could carry messages for businesses, governments and individuals.

By 1884, CPR’s telegraph line had reached beyond the summit of the Rocky Mountains, and the company’s own annual reporting framed it as essential to rapid construction. Then came the milestone: on Sept. 1, 1885, commercial service was extended from Montreal to the Pacific – an east-west communications bridge that effectively pulled BC into the everyday pulse of the country.

Why This Mattered In British Columbia

In the broadest sense, the telegram helped make Confederation real on the ground. British Columbia joined Canada in 1871 with the promise of a transcontinental railway – an undertaking meant to bind the Pacific colony to the rest of the Dominion. The telegraph line running alongside the railway did something similar, but at the speed of information.

For British Columbia, the practical impacts were immediate:

- Markets moved faster. A coastal merchant could learn prices, shipping news, and supply changes without waiting for mail to arrive by ship and rail.

- Government decisions accelerated. Political direction, emergency responses, and administrative orders could cross the country far more quickly than before.

- News became national. Telegrams fed newspapers and wire services, tightening the sense that events in Ottawa – or Montreal or Halifax – were relevant to readers in Victoria, New Westminster, or the growing communities on Burrard Inlet.

Port Moody, Vancouver & A Moving “End Of The Line”

BC’s telegraph story in the CPR era is also a story about where Canada ended – or thought it ended.

The railway’s early Pacific terminus was Port Moody, but it didn’t stay that way. CPR planners ultimately judged Port Moody limited as a long-term terminal site and shifted focus to Granville, soon renamed Vancouver. That decision reshaped the province: a national transportation-and-communications spine now pointed directly at Burrard Inlet, helping turn Vancouver into a city defined by connection – rail, wire, and ocean routes.

You can still feel traces of this history in the Lower Mainland. The idea of being “at the edge” of Canada is baked into local place names, waterfront infrastructure, and the way communities grew around rail corridors. The telegraph line, meanwhile, was the invisible companion: less photogenic than the Last Spike, but arguably just as transformative in daily life.

What We’ve Forgotten & What’s Worth Remembering

It’s tempting to treat the telegram as a quaint ancestor of texting. But in 1885, it was a compression of distance so dramatic it altered the psychology of a nation. British Columbia could do something new: answer back.

And in a province still defined by terrain – by mountains that complicate highways and storms that cut ferry routes – the core idea of the telegraph age still resonates: connection is never just technology. It’s power, opportunity, and belonging – strung, quite literally, across the landscape.