They can be as large as a Smart car, and sometimes they’re even white. Larry Pynn counts the quirky ways of this overgrown national symbol.

It was late evening when a mature bull moose took us by surprise, walking right up to our remote camp in the northern Rocky Mountains. Maybe it was attracted to a nearby mineral lick. Maybe it was emboldened by the presence of horses. Or maybe it had not learned to fear humans.

This was day one into a two-week horseback trip from Stone Mountain Provincial Park on the Alaska Highway (Hwy 97) south to Tuchodi Lakes. We snapped photos as the moose wandered around for a few minutes, then retreated into the waning midsummer light.

Later, while lying in the dark, my friend, Tom Perry, was awakened by a loud snuffling noise and a heavy tread nearby. He unzipped his tent and peered into the pre-dawn gloom. Perry held his breath, and his bladder. As dawn broke, he observed a set of hooves and a massive body and rack—the same moose, back for a second tour of camp before the rest of us woke. Over morning coffee, we delighted in teasing Tom about his animal magnetism.

Moose may be a familiar sight in this province, found in the wild as well as near urban areas, but there are a few facts about them that you may not know.

They’re a big deer

The moose is the largest member of the deer family in North America. Sizes vary widely among the three subspecies found in British Columbia. Shiras’ moose, also known as Yellowstone moose, is found in the southeastern corner of the province and weighs upward of 370 kilograms. That compares with up to 725 kilograms—the weight of a Smart car—for an Alaskan bull moose, found in the northwest. The mid-sized Northwestern moose roams the vast majority of the province.

Moose (Alces alces) are beefier farther north to withstand colder temperatures and they tend to have a darker coat to soak up the heat. The B.C. population fluctuated between 145,000 and 235,000 in 2011, although numbers are thought to have declined. To learn more, the province will spend more than $2-million and radio-collar more than 200 moose to track their movements and investigate their causes of death over five years.

Moose are safer from afar

Moose attacks on humans are rare but do occur, especially when a cow is protecting its calf. Brian Churchill, a former regional wildlife biologist in the Peace country, and two colleagues were investigating the carcass of a collared calf near Tumbler Ridge when someone made the mistake of making a calf call.

“The cow came down and chased us up a tree. We sat there for two hours until she lost interest and wandered off.” Moose use their powerful hooves to inflict damage on wild predators and, sometimes, people. In March 2009 a Prince George man trying to call off his dogs in a wooded residential area behind a Walmart escaped with minor injuries after being trampled by a cow and her calf. As much as possible, it’s best to avoid close proximity. “They’re not a threat if people keep their distance,” observes conservation officer Gary Van Spengen.

Small foes can fell them

Bears prey on newborn moose calves in spring, and wolves feast on adult moose year-round. But the moose’s most dangerous predator is also the smallest: the parasitic winter tick. When moose are inundated by ticks—up to 50,000 or more—they become preoccupied with grooming their coats, resulting in loss of hair and reduced feeding and sleeping. This downward spiral can end with the death of the exhausted and emaciated creatures, sometimes—when there is an outbreak—in very large numbers, with calves proving especially vulnerable. Since the absence of snow after a shorterthan- average winter increases tick populations, the length of winter in an area can be a factor influencing tick infestations along with the density of moose and habitat quality.

Moose get around

Moose are thought to have increased in numbers and expanded their range as landclearing, including logging, created more browse. Moose thrive on the shoots and leaves from shrubs and young trees associated with the early stages of forests; willows are especially important in their winter diet. One study suggesting moose have pushed west of the Coast Mountains in the central and north coast areas since the mid- 1900s quotes Cecil Paul, a Haisla elder, as saying: “Moose were not here or ever a part of stories when I was a child.”

They’re on the menu

Salmon are the lifeblood of Aboriginal people living along the Fraser River and along the coast, but for those in Northern B.C. moose meat is a mainstay, in part due to a severe decline in caribou populations. Chief Roland Willson of West Moberly First Nations, northwest of Chetwynd, explains that the meat can be roasted, boiled, fried, dried, and smoked over a wood fire, or combined with berries and fat for pemmican. Nutritional delicacies such as the brain, tripe, heart, and kidneys are often reserved for the elders. Some band members still use the hides for making moccasins and clothing. Aboriginal people are not required to have a hunting licence for food or to report moose kills.

They’re real Casanovas

In the Royal BC Museum handbook Hoofed Mammals of British Columbia, David Shackleton explains that the fall rut involves the male moose scraping a small depression in the ground, then urinating and wallowing in it. Attracted by the odour, the female will approach to sniff the male, then also wallow. The male then approaches from the rear, sniffs her, and if she urinates, curls his lip to test her estrus status. Then, if she allows him, he places his chin on her rump, mounts, and copulates. “Their breeding behaviour would make Casanova look like a bumbling teenager,” remarks Ray Demarchi, retired chief of wildlife for the B.C. Ministry of Environment. Bull moose ranging in open country can have harems, but in the forest tend to mate with one female at a time—known as serial monogamy. Cows typically give birth to one or two calves in late May or early June after a gestation of eight months.

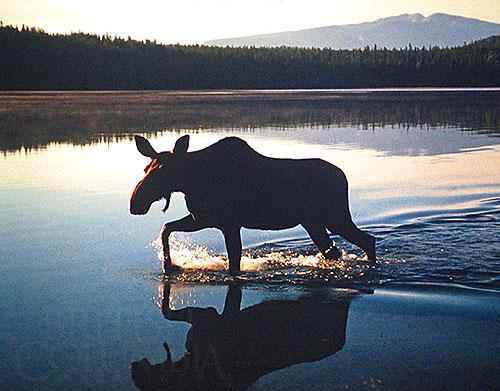

They’re strong swimmers

Moose roam a wide range of habitats, from dense forest to open tundra and even alpine, but are often associated with marshes and lakes. Powerful swimmers, they can dive down more than five metres to reach sodium-rich aquatic plants and stay submerged for 30 seconds or longer. They are known to seek out deep water to avoid predators and can swim distances of up to 20 kilometres.

Moose can communicate

Moose have physical and audible forms of communication, sometimes in combination, according to the Ecology and Management of the North American Moose, by Charles C. Schwartz, Albert W. Franzmann, and Richard E. McCabe. When agitated they can raise the hair on their neck, spine, withers (part of the back), rump, and flanks. They will also drop their ears down and backward. The distress call of a calf is loud, hard, and nasal. An annoyed adult moose may issue a short nasal snort or bark, rising to a loud roar. Cows moan or wail when in estrus. Bull moose clashing antlers (females have none) during the rut can attract other males, and humans, too. Larri Woodrow, a backcountry horseback riding enthusiast from Langley, recalls a trip to the Tetsa River in Northern B.C. in which two bulls could be heard fighting violently in the spruce forest. Then silence returned, and a huge bull emerged from the timber and moved slowly toward two cow moose.

Their greatness carries a price

Far higher numbers of deer are killed on B.C. roads than moose. A study conducted by the University of Northern BC states that between 2006 and 2010, 35,968 deer were involved in motor vehicle collisions, compared to 3,565 moose— though only 25-35 percent of accidents are reported. Moose, however, inflict far greater damage to vehicles and their occupants. An average accident involving moose costs $30,760 (USD), compared with $6,617 for deer, according to studies conducted in Canada and the U.S. Some novel initiatives are underway to reduce such accidents. In the Prince George region, researchers have “deactivated” mineral licks that lure moose to highways by rototilling in rocks, cedar bark mulch, logs, as well as animal and human hair. Other measures include setting up warning signs for drivers with flashing solarpowered LED lights or displaying a cardboard cut-out silhouette of a moose. The Wildlife Collision Prevention Program (wildlifecollisions.ca) also provides a list of critical areas along with peak times of the year and day during which collisions are most likely to occur.

Sometimes they’re white

Fraser Lake has white moose, most often observed in winter on the north shore of Fraser Lake, about 160 kilometres west of Prince George. “They’re not albinos, they’re oddities,” offers Dwayne Lindstrom, mayor of the Village of Fraser Lake. He wishes no harm to come to them, but suggests that if one happens to be hit on the highway he’ll have it “stuffed and put in a museum.” Hunters cannot legally shoot a white Kermode or “spirit” bear, but no such restriction applies to a white moose. The B.C. government only urges hunters voluntarily “not to shoot a white moose due to their uniqueness and viewing values to all people who enjoy wildlife.” Lindstrom is a hunter himself and supports complete protection for the white moose. That would see the “spirit moose” take its rightful place alongside the spirit bear, thereby raising overall awareness for an extraordinary wild animal deserving of iconic status.