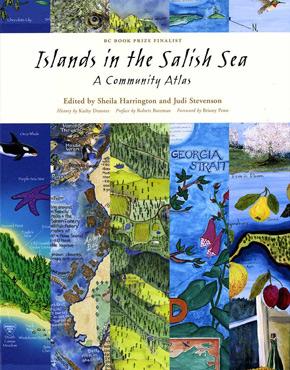

Environmentalist and geographer Briony Penn of Saltspring Island was an early advocate for the naming of the Salish Sea, the international body of water profiled in “Welcome to the Salish Sea” in the Winter 2011 issue of British Columbia Magazine. She was also instrumental in a community mapping project of the area, which culminated in the book Islands in the Salish Sea: A Community Atlas.

“Community maps provide a geographical as well as historical record of what makes a place unique and liveable,” she writes in the foreword. Here Penn explains more about the project.

What are community maps?

“Any map that is done to record and bring attention to places and features that matter to people for non-commercial reasons could be called a community map, e.g., mapping cherished places in a region. It is simply a map that has heart. A map done by a fast food chain, for example, showing people where to buy their product is not a community map—that would be a commercial map. Maps are very powerful tools for selling ideas and what distinguishes different maps is the objective of the mapper(s). Community mappers ‘sell’ the idea of common ties and bonds to a region, whether it is mapping a watershed, wild berry patches, or the local farms. Community maps are often done by local artists to bring life to the maps—what the renaissance mappers called “marrying the microscope to the mandolin.”

When were you first introduced to community mapping?

“Back in 1982, I was lucky enough to go to the UK on a research mission, as part of the Victoria Greenbelt Society’s vision which became the Galloping Goose Trail on Vancouver Island. I met with Sue Clifford and Angela King of Common Ground who were pioneering the use of the “parish map”—local maps done by local artists of each of the parishes of England. Their goal was to bring alive the small, the particular, and the possible rather than the huge, the general and the overwhelming issues of the time.”

What was the Islands in the Salish Sea Community Mapping Project?

“The Salish Sea mapping project was a direct consequence of the Parish Map Project. I ended up doing my PhD in Britain in Geography and came rushing back to British Columbia excited about these ideas. I moved back to my home place on Salt Spring Island where I saw the need for such a project and worked with wonderful community organizers like Judi Stevenson and Sheila Harrington to launch the project. We extended the net of community organizers to the other islands who sourced all the great artists and, voila, the atlas.”

Who created the maps?

“Artists from all over the islands, fishers to First Nations, professionals to young aspiring artists, potters to painters. Most of the mappers were selected by the community organizers either through a competition or acclamation. Each island worked out how to meet their island’s objectives for their map. It was one of the highlights of my life to be in the company of all these amazing people with talents and a love for their homeplace. I believe there is a huge hunger for belonging and place, and localisation as an antidote to globalisation is finally returning as an idea.”

What do you believe was the greatest legacy of the project?

“When I returned to BC, I was also really struck by the lack of particular language around our distinctive landscapes. For example, we had no name for the Garry oak meadows full of camas and other wildflowers that characterized this region, nor was there a name for the Salish Sea—the last unnamed sea in the North America I think! My friend, Bert Webber, a Canadian scientist who was living in Bellingham working on oil spill responses in the marine environment, had gotten tired of the lack of a name to describe our common waters. He worked on the American side, with the Lummi First Nations, to promote the name of the Salish Sea and I worked on the Canadian side, through writing articles, songs with Holly Arntzen, projects with Parks Canada, and making maps from about ’96 on . . . . The greatest legacy, I think, was to boldly promote the concept of the Salish Sea and support elders like Tom Sampson from Tsartlip First Nations who formed the Salish Sea Council—an indigenous, cross-border initiative to improve the health of the Salish Sea—at a time when no one really knew what we were talking about. But here we are several years later with the official name!

I hope people ask themselves two questions: What does Salish mean? And why is naming it a sea important? The answer to the first is the language of the Coast Salish people that inhabited these shores for millennia. The Salish taught that the waters and lands and animals were sacred. I hope that people pause to think about that. The answer to the second is that we live around a sea that is a partly enclosed body of water that is much more vulnerable to pollution and degradation than the open ocean. The water doesn’t flush so frequently and toxins accumulate. Also protected waters like seas are also places of rich biodiversity because there is shelter from the biggest oceanic storms and many animals come in for sanctuary to overwinter, breed and raise young. I wanted people to realise that we share these waters from Puget Sound to Campbell River and we need to look after this delicate but rich, rich sea, like the Coast Salish did for millennia.”