It’s such an exciting time to be here,” says an enthusiastic Jess Freese as we sip coffee at Fergie’s Café on an unusually snowy February morning. The “here,” in this case, is the city of Squamish, British Columbia, as well as Sun-wolf—Jess and her husband Jake’s collective of riverside cabins, rafting tours and farm-to-table fare, located a 10-minute drive from town. And the “time?” That’s a little more complicated.

For years, Squamish has dubbed itself “The Outdoor Recreation Capital of Canada.” With premier rock-climbing, epic windsurfing and kiteboarding, rowdy mountain bike trails, renowned ski-touring and endless hikes all within minutes of downtown, it earned the moniker well. But for much of this time, the town also wallowed in relative tourism obscurity, stuck smack-dab between the major-player destinations of Whistler and Vancouver, each about 40 minutes north or south.

Squamish had a unique problem—its outdoor recreation was simply too world-class. Even the thought of rock climbing on the Stawamus Chief would cause most people heart palpitations; the ubiquitous wind that makes the Squamish Spit a popular kiteboarding locale also brutalizes newbies; and the incredible bike, hike and ski routes are hidden between imposing mountain peaks and within dense, unserviced rainforest. In short, Squamish was no place for beginners. And most tourists are beginners. That combined with a resource industry providing local jobs and one of the world’s most famous tourism playgrounds just 60 kilometres beyond and Squamish was long relegated to “the McDonald’s on the way to Whistler.”

Jump to today, and Squamish is welcoming new restaurants, craft breweries and unique accommodations; the town is exploiting newfound outdoor recreation opportunities as a catalyst for exponential tourism growth; and it is even attracting tech industry jobs and an influx of Vancouverites seeking a slower pace and bringing with them entrepreneurial ideas.

It all happened in just a few years. So what changed?

In some ways, Squamish’s maturity was natural. Take Pat Allan, restaurant director and sommelier at The Salted Vine Kitchen & Bar, which opened in downtown Squamish last fall. A long-time Squamish local, Pat forged his career at Araxi Restaurant & Oyster Bar in Whistler—a prominent eatery considered the finest dining in the resort town. The 40-minute commute (often much more, in holiday traffic or a snowstorm), however, wore him down.

“I wanted a better family life,” he explains, taking time out from the Friday night rush at his popular restaurant to join my wife and I at our table. Without a local establishment fitting to his restaurateur resume, Allan, along with executive chef Jeff Park (also from Araxi) did what any entrepreneurs would—they built their own. “We had long joked about opening a restaurant in Squamish,” he continues. It seemed a laugh simply because nothing like The Salted Vine existed in town—in fact, it still stands alone as the only elevated dining experience in a rough-around-the-edges downtown noted for pub culture and fast food.

As Squamish’s demographics shift toward the younger, The Salted Vine looks to the town’s future. Housed in a 107-year-old building on Victoria Avenue, it offers high-end Pacific Northwest fare such as lamb ragout, oysters on the half-shell and cheeses from as near as Salt Spring Island and as far as France, as well as service and ambience to match. Not to mention the extensive wine list and bar manager Dave Warren’s signature cocktails—the Thai-influenced Firecracker Margarita being among their best.

“You can move to Squamish and you don’t have to leave the urban vibe behind,” says Allan. He loves the local pubs, but he and his partners wanted to offer people a reason to stay in-town for everything from date-night, to girl’s night out, to a casual evening with friends that’s likely to end up at the throwback Chieftain Pub anyway. “We’re even getting people coming from [Vancouver’s] North Shore,” he continues. While recent increases in tourism are great for business, and the presence of his restaurant in turn bolsters tourism, Allan knows he needs strong community support to succeed. “It’s all about the locals,” he says as yet another patron pops by to shake his hand.

Entrepreneurs Jeff Oldenborger and his wife Caylin Glazier have a similar story. They recognized Squamish as a catalyst to fully realize what they saw as the four pillars of a good life: family, health, the outdoors and community. Well, maybe there is a fifth pillar—beer. The duo knew they liked lagers and ales. And, despite having no experience in the industry, they dreamed up A-Frame Brewing Company, with Squamish as a base of operations, while vacationing at their cabin on Okanagan Lake. (An A-frame, of course.) Opened on December 9, 2016, it is the town’s second craft brewery. The first, Howe Sound Brewing Company, is one of B.C.’s oldest craft beer makers and a celebrated innovator in the province’s brewing scene. Which meant the husband-and-wife duo was stepping onto hallowed ground.

“I called [Howe Sound] up and explained what I wanted to do. They were incredibly supportive,” explains Oldenborger as he pours me a flight of ales. Rather than act territorial, Howe Sound Brewing Company helped the upstart brewer negotiate with suppliers and offered advice on both brewing and business.

While A-Frame and Howe Sound are competitors on paper, they offer drastically different experiences. Howe Sound has a pub, event space, hotel and province-wide distribution of their well-known products. A-Frame is a simple tasting room and growlery. (In typical Squamish laidback fashion, there is a children’s play area next to the bar.) With four standards and two seasonal taps, A-Frame is local-focused operation—through, just like The Salted Vine, Squamish’s newfound tourism growth is icing on the cake. A cake that’s about to be split into more pieces—a third micro-brewery, Backcountry Brewing, is set to open this spring.

Back at Sunwolf, Jess and Jake Freese are hoping to capitalize on the increasing visitor market. Thirteen years ago, the couple left a lucrative but unsatisfying life in the U.K. to live the dream as Whistler ski-bums by winter and scuba instructors in Honduras by summer. “I just wanted to retreat to the things I loved,” explains Jess, who left behind a career at the financial firm PwC. (As we savour our sumptuous breakfast prepared by Fergie’s Cafe chef Jason Nadeau, I notice her shirt reads “coffee, mountains & cabins”—the things she loves.)

Once Whistler’s ski-bum party lifestyle wore thin, the Freeses—whose paths had led them to become rafting guides—desired to create something meaningful. They also wanted to stay in the Sea to Sky Corridor they had grown to love so dear. Serendipitously, the “Old Sunwolf,” a collection of rustic cabins set on a scenic but neglected property, was up for sale in Brackendale (a community on the northern edge of Squamish). In 2010, they jumped in headfirst.

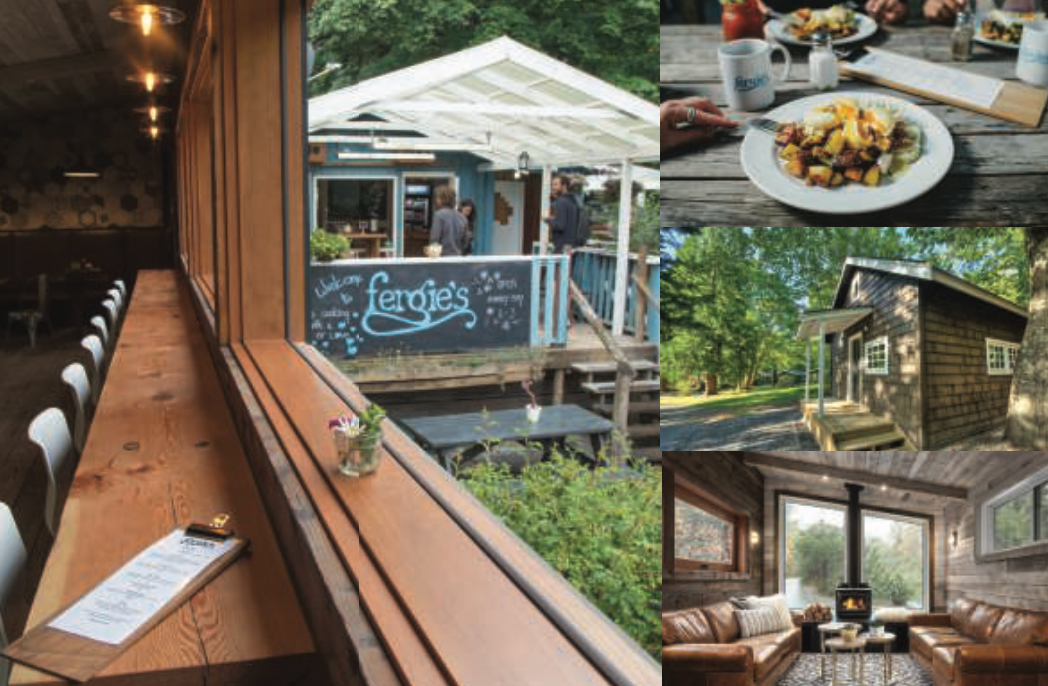

“Jake had never even held a skill saw. He rented a [backhoe] and watched YouTube to learn how to drive it,” Jess laughs. Their first hurdle was getting Sunwolf’s river-rafting tours back in operation. With that revenue-generating business in motion, it was time to renovate and rebuild the cabins, for which they rounded up their equally inexperienced friends for a multi-day re-roofing party. “We had beer and music by the campfire at the end of every day,” recalls Jess, citing such community support as pivotal to launching this business. Next up was Fergie’s Café—to which in 2016 they added a new inside dining area to the formerly grab-and-go/picnic-table digs. Adorned with reclaimed barnwood, warmed by a woodstove and with a captivating mountain vista, it has become the area’s most-loved brunch joint.

Today with 12 nature cabins—the only year-round accommodation of its kind in town—both summer and winter river-rafting tours and an onsite eatery, Sunwolf has become key to Squamish’s tourism industry. It’s so popular, in fact, that Jess tells me some locals even book weekends away here—just 10 minutes from their houses.

“I just feel lucky,” says Jess. “It’s so nice to look back at all your decisions and see they led you here, and you are happy.” Though she adds: “We worked hard for seven years, but we couldn’t have imagined what Squamish would become.”

Pat Allan and Jeff Park, Jeff Oldenborger and Caylin Glazier and Jess and Jake Freese present a similar storyline—a desire to create, connect and succeed, as well as a desire to call Squamish their home. And they all speak of a recent shift in Squamish’s stature. What is happening in this city of 20,000 residents that has inspired these, and other, local entrepreneurs? What is the ignition behind this “exciting time?”

It may have seen its first sparks in 2010, when the Squamish Adventure Centre opened its Douglas-fir doors in anticipation of a visitor influx arriving with the Olympic Winter Games. However, it really changed in 2014 when the Sea to Sky Gondola began shuttling passengers 900 metres up the side of Sky Pilot Mountain, forever altering the destiny of The Outdoor Recreation Capital of the World.

For the first time, recreationists could find a place in Squamish regardless of skill level. The $22-million gondola is unique in Canada—it’s not a ski lift or a sightseeing tram, but it’s also both, and it’s more. In summer, tourists can scoot up through scenic mountain vistas to enjoy anything from a burger on the Summit Lodge patio, to a nature walk open to baby-strollers, to a backcountry hike that will test the legs of any adventurer. In winter, it accesses a tube park, front and backcountry snowshoe trails, cross-country skiing paths and expert-level backcountry alpine touring. (The patio is still open.) Effectively, and for the first time, the gondola opened up The Outdoor Recreation Capital of the World to enthusiasts—that means tourists—of all ages and all abilities.

Within a year of the gondola’s opening, Squamish was named one of the “52 Places to Go in 2015” by The New York Times, an honour usually reserved for major-players like, well, Squamish’s two neighbours. In January, the gondola welcomed its one-millionth rider. And in the time between the gondola’s opening and today, the meteoric rise of property values in nearby Vancouver has flushed young professionals out of the Big Smoke and into the shadow of The Chief, only adding to local inertia.

Gusts are rocking our gondola car back and forth as we climb hundreds of metres over snowy trees and granite en route to the summit from the upload alongside Highway 99. It’s February, and more than a metre of snow has collected at the Summit Lodge. Within our tram sits a collection of snowshoers, one cross-country skier and two avalanche-transceiver equipped alpinists. Half local, half from Vancouver; all chatty and excited to be here. It used to be that no one went to Squamish in winter. Today, it’s one of Vancouver’s top snow-day getaways.

My wife and I were early adopters to the Sea to Sky Gondola, having bought winter passes the first year it opened. During summer, we’ve enjoyed all-day hikes like Al’s Habrich Ridge Trail, which extends for 12 kilometres into the rugged backcountry of the Coastal Range, as well as simple walks-with-a-view. And we’ve been amazed at the hundreds of tourists, their voices chorusing like the Tower of Babel, who flock from Vancouver or Whistler when just a few years earlier Squamish would have been lucky to catch them at the drive-thru.

As local entrepreneurs have also discovered, the gondola has shone a new light on what Squamish always offered. In recent years, I’ve hiked more in Squamish than I ever have before—whether from the gondola or at the classic Stawamus Chief—spent more time swimming at picturesque Alice Lake in summer (located just north of town) and even taken kiteboarding lessons at Squamish Spit after years of putting it off. Put simply, the presence of the gondola has placed Squamish indelibly front-of-mind for every Vancouverite.

The Sea to Sky Gondola allowed Squamish—“the McDonald’s on the way to Whistler”—to rightfully claim its independence. And bolstering operations like Sunwolf, The Salted Vine, A-Frame and others are taking the town one step further. Thanks to such community-minded entrepreneurs, in just a few years Squamish has quantum-leapt from “the town with the gondola” to a freestanding vacation destination and an attractive home base with blue-sky opportunity. In short—Squamish is just Squamish now. No explanation required.

If You Go

Stay

Scenically set on two wooded hectares at the confluence of the Cheakamus and Cheekeye rivers, Sunwolf offers 12 cabins, river-rafting tours from mild to wild and onsite dining.

Eat & Drink

Located at Sunwolf, Fergie’s Café serves hearty locavore breakfast and lunch—dine outside underneath the walnut tree or within the new woodstove-warmed indoor space.

Pick up a coffee and cookie to go at The Crabapple Café, or grab a table for breakfast, lunch or dinner at this lively locals’ joint.

The Salted Vine Kitchen + Bar stands alone as Squamish’s finest dining experience, yet also maintains a casual atmosphere suited for anything from date night to après-hike drinks.

It would be easy to miss A-Frame Brewing Company at its location in an industrial park on Queens Way—but the bright and welcoming tasting room and six brews on-tap are worth the jaunt.

Producing craft beer before anyone even called it “craft beer,” Howe Sound Brewing in downtown Squamish has been mainstay in the B.C. brewing industry for more than 20 years. Dine and stay onsite. howesound.com

Play

Glacier Air offers a variety of flight tours—from mellow flightseeing in a Cesna 206 to an aerobatic experience in their Super Decathlon that will test your nerve with loops, barrel rolls and hammerheads. (They’ll even let you take the controls.)

The Sea to Sky Gondola is the number-one attraction in Squamish, offering year-round alpine experiences for all levels, plus onsite licensed dining and special events.

For More Info

Contact Tourism Squamish for more information or to book tours.