I’m drawn to the old towns, the beautiful but lesser-known places where industries like logging, mining and fishing once thrived. Often remote, often surrounded by mountains, sea or forest, sometimes scarred but also resilient, these places and the pioneers who inhabited them have been vanishing. Replaced by gentler industries and a different mindset, the frontier towns are being ‘done over.’ It’s a good thing, my head knows, but my heart is drawn to the disappearing places where, as a teenager, I used to ship mining and logging equipment from my father’s fledgling business, places like Crofton.

OK, you know I’m joking, right? When it comes to Crofton, metropolis is a bit of a stretch, but the town is on the move and growing, shifting from resource-based industries to a commercial, recreational and retirement hub.

There’s no question that this previous site of extensive logging, mining, smelting and a mill, Catalyst Paper, is in beautiful surroundings. A deep bay fronts its streets, with warm water perfect for swimming, crabbing and shrimping; mountains and forests are perfect for hiking, and the climate is temperate. Overlooking Stuart Channel and Salt Spring Island, it’s the perfect location for those drawn to the sea and its pastimes. It’s also close to the verdant and fertile Cowichan Valley, with its wineries, farms, markets, festivals, galleries and musical events. Catalyst Paper still employs many of the locals and still sends its smoke and pungent smell into the air, but only when the winds blow in a northerly direction do Crofton villagers notice. Until recently, the mill has probably also been a major factor in keeping housing costs lower than surrounding areas and hence more affordable for young families. But times they are a-changing. Catalyst is now the last operating paper mill on the island since Port Alberni closed and Campbell River shut many years ago and Nanaimo’s Harmac mill produces only pulp, not paper.

Dan Robin has lived in Crofton for 35 years. He has been a director at the very active Crofton Community Centre for seven years as well as a Board of Variance member in North Cowichan. He tells me that right behind his property there are 200 houses going in and that there is speculation that a 50s-plus development will be built in the town next year. Municipal plans may also come to fruition for a marina and shore development to happen in the future. His enthusiasm for his community and its potential is considerable:

“The town is growing and it’s a great place to live. It’s quiet, there’s very little traffic here and it’s safe for people to walk their dogs. People feel safer in small communities. There’s also good anchorage and hikes and swimming beaches. Lots to do.”

But that’s in the future and I want to learn about the past. It’s time then to enter the pretty little red and white former schoolhouse situated on a slight rise in the small park near the docks, overlooking Osborne Bay. It’s well loved by pigeons enjoying the water views from its roof and obviously by locals too, who saved it from demolition and gave it new life as the museum in 1973. “It was still at its old location on Emily Street but moved down to its new location in 1986,” the Crofton Old School Museum president, Doreen Knight, had explained earlier. “Our fathers and grandfathers’ pictures are in the museum’s class photos as are mine and my sister’s.” Her sister, Laurie Pauls, is the society’s vice president.

Now we’re greeted by retired archivist, Larry Harris, who has kindly come out of retirement to revisit his beloved museum as well as to show us around. Just inside the door of the tiny building is an old organ with a display of archival photos above it:

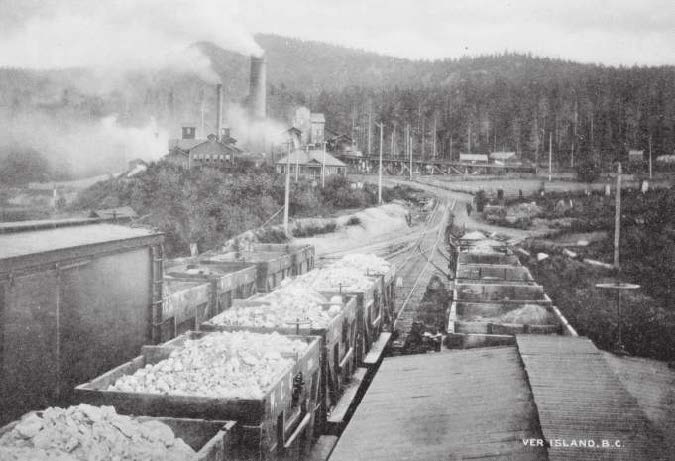

“Look at this photo,” he tells us after introductions. “Now if you keep that in your mind and then turn this way, that is exactly what you would have seen out there in 1903.” We look at one of the seven archival photos and then turn and look out the window at a very different, softer scene without smelter or industry.

He points to another photo: “And you see that building there? Upstairs is where the original school was.” It was just a room in a vacant store in the Croft block on Joan Ave. in 1902 and home to 27 school age children and their first teacher, Mrs. Bertiaux.

With new families arriving regularly, however, an actual school was definitely needed, and it was built on land donated by Henry Croft, the town’s founder, and on April 1, 1905, it was opened to great fanfare and celebration. The school contained a pot-bellied stove with wood and water carried in by the students and hosted annual Christmas concerts and other community events. It was used as a school until 1948. “It was originally up on the hill,” Harris says, pointing to an interesting shot of the wee structure on the move. “Then it was moved across the lot to make an area for the new school that was built in the ’50s, and then it was moved to its present location.”

Upon his retirement 19 years ago, Harris himself made a short move across Stuart Channel from Salt Spring Island to Crofton, drawn by the dramatic difference in real estate prices between the neighbouring communities.

Now he’s pointing to another photo showing an early, short-lived industry that nevertheless left its mark. “That was the smelter. And this was the beach.”

The beach has also changed greatly since that photo. The copper smelter that operated here in the early 1900s produced a black ‘sand’ that still covers some of the shoreline. “The black slag will be part of a beach remediation in the future of the waterfront redevelopment,” Dan Robin had told me earlier.

Harris takes us to an intricate scale model of the smelter and points: “This is the trestle that they put over the E & N railway. These cars were coming from the dock. That’s the dock there. For the last two years the mill was owned by Britannia Mines. They provided ores for the smelter. Now here, just so you understand the smelter a little… The ore would be crushed and go into the smelter there.”

Harris knows his stuff and we’re lucky to have him as our guide this morning. Although he has recently retired from this labour of love, we can see it’s still important to him. “You see this little corner here?” It’s a small jumble in the corner, filled with treasures. “That’s my archives. I spent three to five years scanning all the photos in the museum, thousands of them, and putting them in digital form.” He wipes down a cobweb. I wonder if he will ever truly retire.

Now we’re learning all about this community’s history, from its early First Nations’ roots to its present. The Halalt First Nation lived in the area for many thousands of years and a now extinct group known as Tliyamen (People of the Mountain) used to live here but vanished several hundred years before the explorers and later the settlers arrived. Settlers cleared the land in the mid 1800s and began farming and cutting lumber. In 1873, what later became Crofton was incorporated as part of the District of North Cowichan, and in 1882 the man who gave his name to this town arrived in Canada.

“Henry Croft was born in Adelaide, Australia, hence the name of the street back there,” Harris tells us. “He emigrated to Canada and came to Vancouver Island in 1882. He was not a good businessman. Soon after he arrived, he got into business with the Dunsmuirs, and he opened a lumber mill in Chemainus. The sawmill failed. During that time, Henry married Mary Dunsmuir, 17 years his junior, and he created Crofton and started the smelter. Sometime around then the Dunsmuir family business transferred from Robert to James Dunsmuir, the son. Henry and James did not get along. One of the reasons why was that Henry had decided to build the smelter here and the only way he could get the ore from Mt. Sicker was to build a trestle across the E & N railway. James, who owned the railway, was not going to allow this, so Henry took James to court. The court ruled for Henry. So then Henry has got this smelter being built and James decides to build his own smelter in Ladysmith. Not only that, but they are both using the same vein in Mt. Sicker, so you have the two of them working against each other, plus the drop in ore quality, plus the price of ore dropping, collapsing both smelters.” Poor Croft, after founding the townsite named after him in 1902, and building a town with every amenity for his workers including an opera house, those copper prices dropping drastically in 1907 were the final straw. The smelter only operated for six years, the last two under the ownership of Britannia Mines.

We’re intrigued. Who knew that Croft had married one of the sisters in the famous Dunsmuir family? And who knew that two intelligent businessmen could be so at loggerheads as to destroy each other?

After this, the short-lived company town fell on hard times, with its hardy residents turning to logging and fishing until 1956/57, when a large pulp and paper mill was built—the mill still operates today, although renamed in 2005 as Catalyst Paper.

A substantial part of the museum is taken up with two rooms that fascinate me—the old schoolroom with its desk, old volumes of readers, large bell, blackboard and photos of graduating students, and the old pioneer kitchen with the bread rising atop the old stove, the old washing tub in the corner and all the old utensils hanging above the stove.

“Here’s something every household would have had back then.” Harris points to the 5¢ Maclean’s magazine. “Everything in the museum has been donated by locals.”

We wind up in the school room and sit at the tiny desks as he continues more of his history lesson: “When the paper mill went in December 1957, that’s when Crofton started to develop and lots of homes were built. In the 1970s, the majority of people were mill workers. In the 1980s, Crofton became a young family community. Young families could come in here and buy houses for next to nothing as people moved out to other areas, and now it’s developing toward an older community,” says Harris.

I wish I had remembered to bring an apple. This school master has had some slow students today but has been very patient. As we say our goodbye and thanks, we wish the Museum Society luck with finding more volunteers so they can keep this precious little building open and this history alive.

We still have some time left before we take the ferry. Good!

That will be time then to take the sea walk, about 1.5-kilometre return, to Crofton Beach where we can look at some of E.J. Hughes’s artwork. This famous Duncan artist adored Crofton and often painted the bucolic scenes here. His estate allowed two of his paintings to embellish the metal power box and pump enclosure found here at the south end of the sea walk; it’s the only outdoor wrap of his work found anywhere, according to Robin.

Now an early dinner of crab cakes and calamari at the restored Osborne Bay Hotel, before we board the ferry. The spacious pub has been transformed into the perfect live music venue and we’re told there’s a sold-out concert tonight after the venue’s long closing due to Covid. Prior to then it had become a popular ‘go to’ place for live entertainment in the valley and it looks as if people can’t wait to get back.

I take a last look at a Crofton on the move as the ferry pulls out with us aboard. I’m glad I got to spend time here now, before it reaches metropolis status.